I do a lot of game design seminars and I always meet “The Guy.” He always says the same thing, too. He raises his hand and says, “I’ve been designing a roleplaying game for twenty years now…”

I stop him. Right there. I know exactly where this is going and I need to stop it before it gets any further. I say, “In twenty years, I’ve designed almost thirty roleplaying games. You need to crap or get off the pot, pal.”

That’s usually when The Guy gets up and walks out. And in twenty years, he’ll still be designing the same game. He’ll never be finished.

That’s because he’s unwilling to do the hardest part of design or writing or painting or anything else: letting it go.

I told Mike Curry and Rob Justice this. “Every day, you wake up and know how to make your game better. Every day. Even the day after you sent it to the printer. Even the day after it shows up in bookstores. Even a year after that. Every day.”

The hardest part is letting it go.

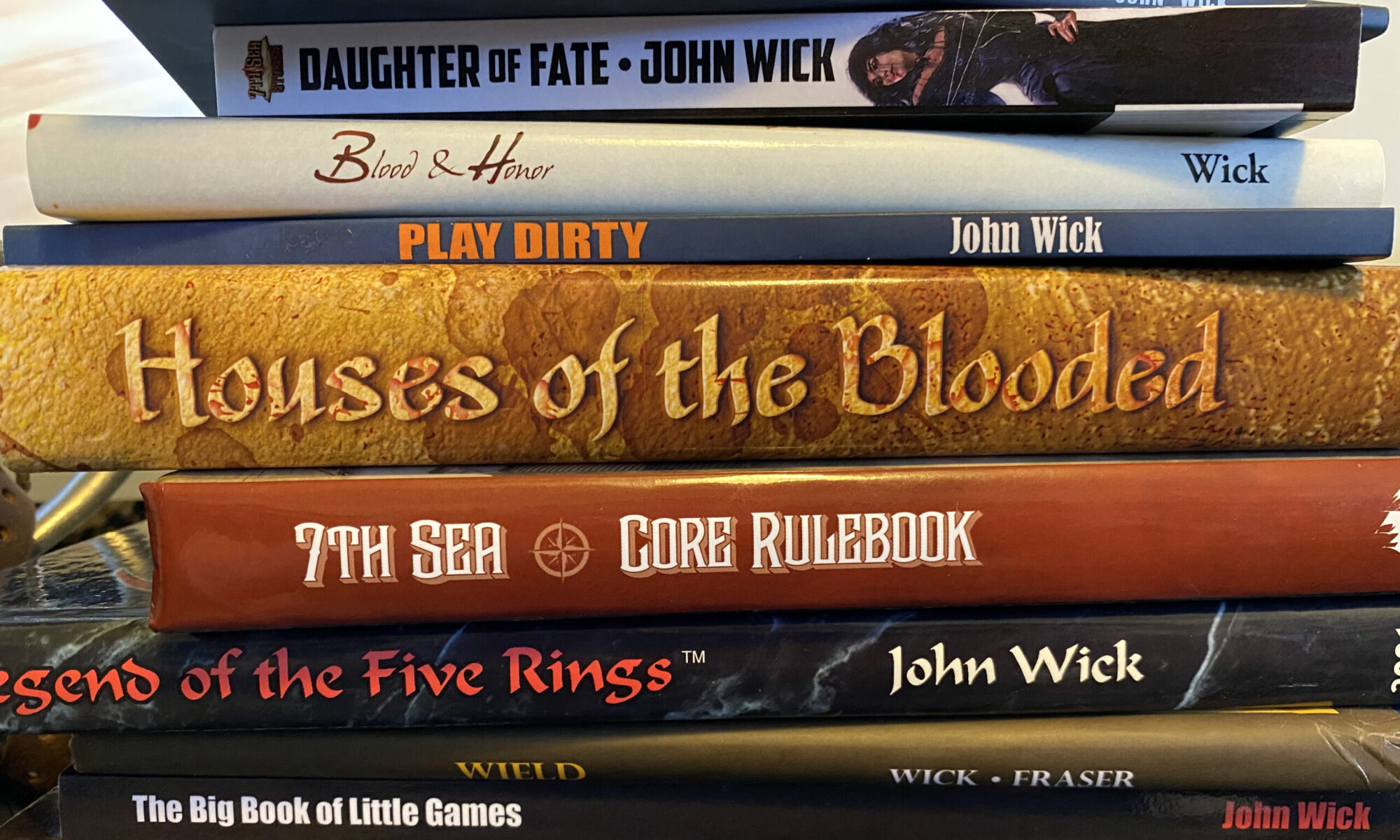

I’m elbow deep in the second draft of Born Under the Black Flag, the second 7th Sea novel. The first one was damn hard. This one was easier. Not a lot easier, but I did a few things I did not do with the first novel. First, I made an outline. Black Flag jumps back and forth through the life of Thomas St. Claire, a pirate in the world of Théah, and I wanted to know where the past and present were going to be. I outlined the chapters on index cards and put them down on the floor with numbers. Then, I picked them up in the order I wanted the novel, giving them letters. I shuffled them around a bit, scratched out some numbers and letters, and when I was finished, I started writing.

I finished just as my deadline hit. I mean, on the same day. Daughter of Fate—the first novel—got pushed back 30 days because I wasn’t finished with it. But St. Claire had a goal, a simple goal, and he was able to reach it because he was willing to spill blood to do it.

First draft done, I sent it off to Amanda Valentine and take a year end vacation, not thinking about the novel for a while so I could approach it with new eyes. Also, I spent some time doing research and reading Patrick O’Brien.

I knew a novel about pirates would need some O’Brien in it. There was already a little—maybe 1 O’Brien’s worth—but I wanted more. Not a lot more, but enough to satisfy myself and the other fans of his work.

O’Brien was the author of the Master and Commander novels—among others—and his storytelling made my heart ache. I couldn’t capture the same authenticity he did—I simply did not have the level of knowledge he had—but I wanted to make sure the nautical elements felt authentic enough.

I told Amanda that when I sent it off to her and she said she would help me out. She had a couple of friends who were O’Brien fans, so when I finished the second draft, she would hand it over to them for feedback.

Last night, I was going through her edits, making changes both big and small, when it came time to introduce the first ship in the book. And this is where I needed to raise the O’Brien Factor. I spent an hour and a half writing a single paragraph. One hundred and thirty words. I wanted them to be the right words. To make St. Claire’s inspection of the ship feel authentic.

Ninety minutes on those words. It was some of the hardest writing I’ve ever done. But I went to bed happy. This morning, I sent them to Ben Woerner who gave me feedback and added a little bit about hammocks. And then, I read it back to myself—out loud. And I was happy. Damn happy.

The Galente was a fluyt out of Vestenmennavenjar. A merchant ship smaller than those from Montaigne or Castille, clearly influenced by recent Avalon designs. The ship was round like a pear when viewed from the fore or aft and the forefoot had greater rake. Despite its size, she could handle shallower waters than most and the aftcastle was tall, giving plenty of room to the officers and the captain. A sure sign of vanity. The masthead caps were wide and she had little room for cannons. All of it was for crew and cargo. Her rigging was designed to minimize the first of them. She was tall and proud, few guns. And she was fast. Damn fast. Just a few carpenters and the right directions, and she’d be a fighting ship in a month.

After I was done, I sent the words to Jessica. She’s my Jane Austen fan. I sent them along with the request, “Please tell me if you get lost in the jargon.” I wanted to make sure there was just enough she could understand what was going on. She sent me this reply:

This is the sort of paragraph I skip when reading. If a fluyt is a real ship, then I don’t want someone spelling it out for me in text. That’s what Wikipedia is for. Talk about the significance that whoever’s POV would be considering.

Things like “A sure sign of vanity” are hints of a good direction. I want to hear the captain (or whoever) size her up, like a sailor would. I know no one knows what a fluyt is anymore, but ignore that. hide the information in the captain’s evaluation of his dreams and plans for her.

A merchant ship means he can hide his nature. That should be emphasized rather than comparing it to other nations.

A sure sign of vanity, but he could afford that. or maybe it would extend to his men, proud to have such a vessel. They will work harder.

I don’t know. But make it personal. Make it real. This is a text book description. Jargon smargon. It’s missing the people and the reasons.

Needless to say, I was heartbroken. I loved those words. I worked hard on those words. Dammit. DAMMIT.

Okay, okay. Take a breath. You know why you’re upset. You know why.

She’s right.

So, after stomping around the room for a little while, I set myself back behind the keyboard and began editing. Looking at Jessica’s feedback and using it. And what I got, after another hour of work, was something better. Not just better, something that Ben Woerner said “gave me chills” after reading it.

Yeah. It was better.

I wasn’t The Guy. I wasn’t going to walk out of the room when someone challenged me. I was going to listen and think.

And let it go.

St. Claire walked along the Galente, his eyes and mind taking in all the details. She was a fluyt out of Vestenmennavenjar: a merchant ship smaller than those from Montaigne or Castille, clearly influenced by recent Avalon designs. She was round like a pear when viewed from the fore or aft and the forefoot had greater rake. That meant he could sail her in shallower waters, hiding behind islands from larger ships. He could sail her up rivers, giving him access to ports and escape routes larger fighting ships could not manage.

The aftcastle was tall, giving plenty of room to the officers and the captain. St. Claire snickered. A sure sign of vanity on the part of the captain. Made the officers’ cabins easy targets for other ships. That would have to go.

She had little room for cannons. Only six per side. Instead of cannon decks, the Galente had room for cargo. She was a merchant ship, after all. Claire didn’t need many more guns, what he needed was speed, and the Galente had plenty of that. Her rigging was designed for minimal crew and outracing pirates. She was fast. Damn fast.

He knew what he had to do. Lose some cargo space with double hammocks and she could carry plenty of fighting men along with a small working crew. Add chase guns to the fore and aft, keeping sharp shooters in the rigging. Hiding in shallow waters at night, waiting for larger ships to go by, sailing right up to their hulls, moving so fast, the enemy’s cannons would fire too long, splashing cannons behind them. Then, unleash the marines. If he got that close, most ATC ships would surrender without ever firing a shot.

Just a few carpenters and the right directions, and she’d be a fighting ship in a month.