If you play roleplaying games, you owe Greg Stafford. You may not even know it, but you do.

Greg was brilliant. He was ahead of his time. You know the Stafford Rule? Every game designer knows the Stafford Rule:

“If you believe you’ve come up with a clever mechanic, Greg Stafford already did it.”

You know how brilliant Greg was? Let me show you how brilliant he was.

In Runequest, one of the things your character can do is sit with a shaman and take a spiritual trip to the God Realm where your character walks in the footsteps of an ancestor or hero. You have an adventure, then return home transformed by the experience. Your character lives the story of the hero, and having that experience, and being changed by that experience, returns to the real world a better person. That’s one of the things you do in Runequest. That’s 1978. While Gary was making sure his falling rules comported to reality in his little tactical simulation game, Greg created the perfect metaphor for what roleplaying games could be: a mythological and transformative experience.

You go into the God Realm, walk in the footsteps of the hero, and come back transformed. Can you come up with a better metaphor for roleplaying games? No, you can’t. Nobody can. And Greg did it in 1978.

Greg didn’t just write about being a shaman, Greg was a shaman. Remember the solar eclipse of 2016? At the end of Gencon, I was able to tell this story without making up a single word. I went to the Chaosium booth to say goodbye to Greg. Unfortunately, I missed him. He was in the air, flying to a secret location to perform a shamanistic ritual during the solar eclipse. I am not making any of that up. It’s the absolute truth. Not a word of what I wrote is fantasy or fiction. Greg was part of a magical ritual during the solar eclipse. I like to tell people that the reason the sun returned to the sky is because of Greg. And you know what? That part of the story is true, too.

He created Glorantha, the greatest fantasy world ever. Yeah, I usually try writing in E-Prime, but I’m not today. Glorantha is the greatest fantasy world ever. You can have your Middle Earths and Narnias and Krynns and Rokugans or whatever else you got. If you don’t know Glorantha, you are missing out. Middle Earth is a fantasy world designed by a linguist. Glorantha is a fantasy world designed by a mythologist. You go get the newest edition of Runequest. And I mean right now. You’ll see what I mean.

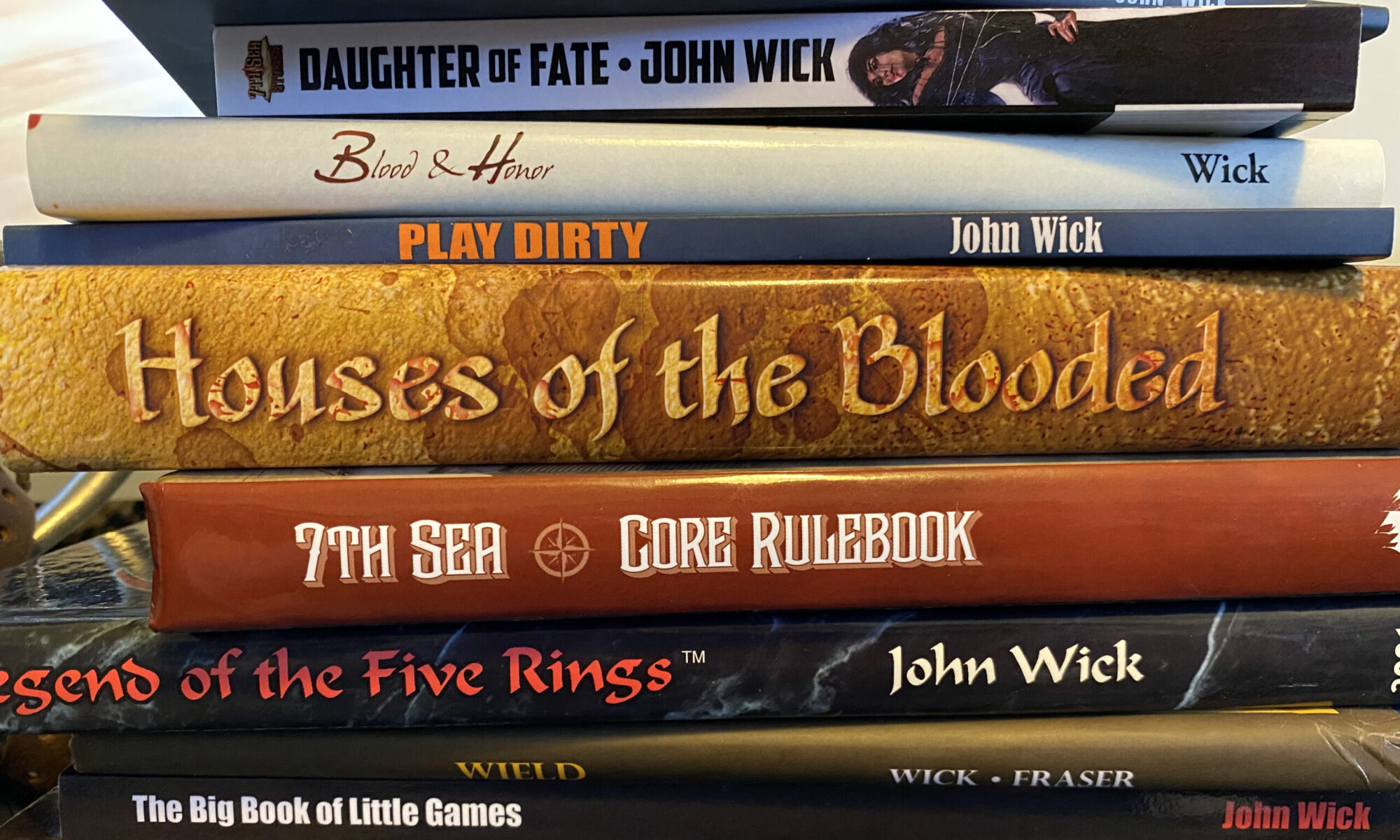

And hey, Legend of the Five Rings fans: you owe Greg, too. You know why? Because the original L5R RPG was just me cribbing from Pendragon. If there was no Pendragon, there’d be no L5R RPG. And you also owe him for something else. You recognize this guy?

Yeah, that’s Kakita Toshimoko, the Grey Crane. The mentor and sensei of Doji Hoturi, the Crane Clan Champion. You know why he’s called “the Grey Crane?” Because that’s my nickname for Greg. Greg Stafford is Kakita Toshimoko, mentor and sensei. My mentor and sensei. It was my way of tipping my hat to Greg, letting him know how important his influence was on me. When I published Orkworld, I dedicated the book to him. It seemed only fitting.

And speaking of Pendragon…

I love Glorantha. I love Runequest. But Pendragon is, without question, the most important RPG I ever read, played or ran. Not Call of Cthulhu (my first RPG), but Pendragon. It showed me how a game could embrace themes and reflect them as mechanics. Every mechanic in Pendragon invokes an element of Arthurian myth and puts it right on your character sheet. You know how knights sometimes go mad, throw off their armor and run into the woods, vanishing for a year? That’s in the game. You know how knights fall madly in love at first sight and do stupid things because they can’t control themselves? That’s in the game. You know how a knight seems to go stronger because of his fame? That’s in the game. You know how the sons of knights take on the traits of their parents? That’s in the game. And you know how women seem to be playing by a different set of rules entirely? That’s in the game. You name an important part of Arthurian myth and I can show you—on your character sheet—how it’s a part of King Arthur: Pendragon.

KAP showed me the kind of game designer I wanted to be. I didn’t want to make rules that accurately reflected the realities of combat so I could create authentic tactical situations. I wanted to tell stories with my friends. Greg’s games are about giving you mechanics that help you tell stories. And he was doing it before the whole “story game” movement came along.

I look at games like Mouse Guard and I see the influence of Pendragon. (And I know the influence is there because I’ve talked to Luke about it.) And I hear gamers talk about how new and innovative and different it is. Yeah, see the Stafford Rule above. Greg was there first.

I see games like Apocalypse World and hear people talk about how it revolutionary its approach to task resolution is. See the Stafford Rule above. Greg was there first.

He was there ahead of us all. Making games that threw away notions of “game balance” or “simulationism” or any of that crap. Greg was a shaman. And he knew the GM’s job was to take the players’ hands and lead them to the God Realm where they could walk and talk with heroes, then come back transformed by the experience.

I am who I am because of Greg. The Great Shaman of Gaming took my hand and led me to the Hero Realm.

Then, he let my hand free and said, “Go play.”

I was never the same.

I owe Greg Stafford. We all do. And it’s a debt we can never repay.