(Be sure to read the counterpart piece: The Best Adventure of All Times)

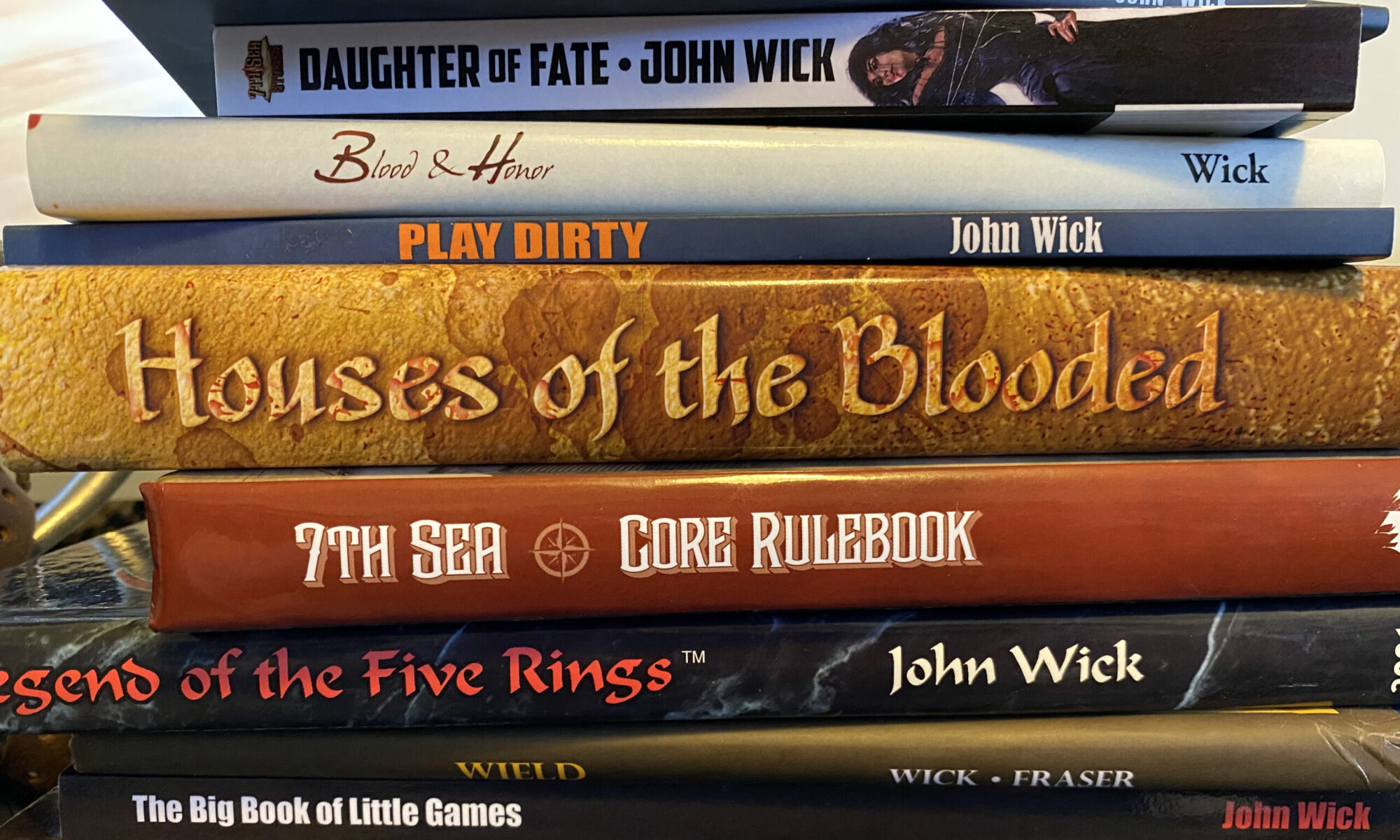

This, right here, is a symbol. A personal symbol of mine. It represents all the wrong, backward thinking that people have about being a GM. I first encountered it in the early ’80’s when I was a player and not a GM. I didn’t have the actual adventure, rather, I heard about it from someone else.

This, right here, is a symbol. A personal symbol of mine. It represents all the wrong, backward thinking that people have about being a GM. I first encountered it in the early ’80’s when I was a player and not a GM. I didn’t have the actual adventure, rather, I heard about it from someone else.

“Have you heard about the Tomb of Horrors?” they asked me.

I shook my head. “No.”

“It’s supposed to be the deadliest dungeon ever made!”

Now, at the time, that sounded impressive to me. The deadliest dungeon ever made? Something I’d have to check out.

For those young kids out there reading my blog, you may not know this, but gaming stores didn’t exist back when I stared playing. No, we had to hit up hobby shops. Places with model trains, model planes and the like with the gaming stuff shoved in the back corner, away from the sight of god and man. That’s because Oprah Winfrey told all our parents that D&D was out to turn us all into Satanists.

You couldn’t ask them to order anything. You couldn’t ask the store owner anything really and expect an intelligent answer. Most of them didn’t know what they were ordering. But when a shipment of stuff came in, we gamers bought it all. We had no idea what anything was. It didn’t matter. You bought what you could get and that was it.

(Years later, I could head over to Uncle Hugos or The Source in Minneapolis. But that was way beyond the days we’re talking about now.)

So, when I heard about The Tomb of Horrors, my little 12 year old brain hit overdrive. The deadliest dungeon ever made! Oh, how I’d love to put my players through that kind of torture!

One day, I hit up the hobby shop to see what random pile of stuff the owner ordered. Flipping through the thin booklets, looking at the covers, reading the text on the front and back, figuring out what I would spend my $10 on this week, I stumbled across a pamphlet a little thicker than the rest. It had a deep green cover with a brilliant Jeff Dee illustration. (Jeff has always been my favorite D&D artist.) And there, in bold type across the top, I read the words…

Tomb of Horrors.

It said, “An Adventure for Character Levels 10-14.” I had players with characters level 10-14. What a coincidence! I grabbed it—knowing it wouldn’t be in the store for ten more minutes if I didn’t—and paid the guy at the front, ripped open the plastic and started reading it right away.

My twelve-year old brain started firing on all cylinders. The adventure came with a booklet of illustrations (damn fine ones, if I do say so) so I could show the players scenes from the tomb as they tried to find their way to the secret vault holding both a vast amount of treasure and the deadly lich lurking there. As I read through the pages, I soaked up the details of all the deadly traps, noting the lack of almost any monsters. And, to be honest, the monsters were pretty much push-overs. It was the traps that would make this little poison morsel so wonderful!

I couldn’t wait until Friday.

Friday came. My players sat down with their characters, unknowing of the unholy dangers waiting for them. I kept the adventure in my backpack, my usual notes on the table. And, I began the evening without even mentioning the tomb. No, they went along their usual adventuring ways, helping out villagers and farmers, tackling bandits and evil wizards. The standard fare.

But I knew the thief in the party was big on collecting maps. So, when they came across a small village with an old, retired wizard with scroll collection for sale, both my own wizard and thief were equally intrigued. Tucked among the scrolls was an old hand-drawn map. “What’s this?” the thief asked.

The wizard’s eyes went wide. “No!” he said. “Don’t take that! There’s nothing but death and doom for you there!”

My heroic adventurers inquired further and he warned them. “That map leads to an ancient place… a place where my friends all died horrible deaths.” (I emphasized Horror there, as foreshadowing.)

With that, I knew I had them. They bought the map, despite the warnings. The wizard said, “That place killed everyone I ever loved. I pray you do not meet the same fate.”

They ignored him. Of course they did.

They followed the map. I led them across a few awful places, ambushed them with a few awful monsters, led them to a mountain range covered in snow, and there, they discovered a single tunnel leading into the rock.

That’s when I took the Tomb of Horrors out of my bag. “And we’ll be playing this… next week,” I told them.

The reaction was better than I expected. A scream so loud, it invoked angry parents.

Yeah, I made them wait a week. And for those seven days, they bugged me. Prodded me with questions. I said nothing. I gave them nothing. They knew we were about to go through The Deadliest Dungeon Ever Made and they were ready for it.

Except, they weren’t.

That Fucking Mouth

A week later, my players sat down at our table and we began exploring the dungeon.

I use “began exploring” because didn’t finish. The entire session lasted… maybe twenty minutes.

My players were lucky enough to choose the long corridor in the middle. And they…

Oh, wait. I should say something here about spoilers. Yeah, there’s spoilers ahead. As in, I’m about to tell you how and why the dungeon works. And you know what?

YOU SHOULD KEEP ON READING.

Regardless of whether or not you’ve ever played the Tomb of Horrors, plan on playing the Tomb of Horrors or never intend on ever playing through the Tomb of Horrors, you should read every damn word. Every damn word. Because this entire essay is a WARNING.

THIS IS THE WORST, SHITTIEST, MOST DISGUSTING PIECE OF PIG VOMIT EVER PUBLISHED. AND EVERY PLAYER AND GM SHOULD KNOW WHY SO SOMETHING LIKE THIS NEVER HAPPENS AGAIN. IN FACT, I’M PUTTING THE SPOILERS IN BOLD RED SO YOU CAN SEE THEM.

Anyway…

My players picked the entrance with the long corridor rather than the two other entrances which are instant kills. That’s right, out of the three ways to enter the tomb, two of them are designed to give the GM the authority for a TPK.

Because that’s making sure your players are having fun.

They went down the long corridor, read the useless riddle on the floor, cautiously avoided all the pit traps and made it to the end of the corridor where they found a misty archway and a green devil’s face. The devil’s face has an open mouth just big enough for someone to fit inside. The booklet told me to say that. Told me to encourage players to climb in.

Problem is, that devil’s face is an instant kill. That’s right. No saving throw, no hit point loss, nothing. You’re character’s dead. You’re welcome.

Because, you know, that’s making sure your players are having fun.

One of my players had his character crawl into the mouth. The actual text from the adventure:

The mouth of the green devil’s face is the equivalent of a fixed sphere of annihilation. Anyone who passes through the devil’s mouth appears to simply vanish into the darkness but they are completely destroyed with no chance to resist.

After he went into the mouth, I said, “He vanishes.” That’s it. I said nothing else. Because that’s what the adventure encouraged me to do.

Then, one by one, my players each had their characters climb into the green devil’s face. And one by one, their characters were irrevocably killed.

By me. I did it. I killed their characters. No saving throw. Nothing.

And… forgive me, Discordia… I enjoyed it. I loved it. One by one, I killed each of their characters. My first TPK.

When the last character climbed in and was utterly destroyed, I jumped up and laughed at all of them. “YOU’RE ALL DEAD!” I shouted.

They looked at me confused. One of them asked, “What are you talking about?”

I read the text to them. They didn’t believe me. I showed the text to them, laughing.

“You guys didn’t even make it passed the first corridor!” I said, laughing in their faces.

It was at that point one of my friends—someone I had known for three years—punched me right in the face. Then, he jumped on me. Kicking me. My other friends had to pull him off.

This was the second week in a row we invoked the appearance of parents.

I should say that the next Monday at school was rough. As a geek, I had precious little friends. That Monday, I quickly discovered I had none.

Bashful and lacking any kind of the confidence I would find later in life, I was unable to summon the courage to apologize. I spent the rest of that year without any friends at all. They continued playing games. I spent the rest of the year just reading. Alone.

And the thing I read the most was the Tomb of Horrors. I kept going back to that adventure, wondering what I did wrong. Why did my friends hate me so much? They knew we were going into The Deadliest Dungeon Ever. They were prepared for the consequences. They knew their characters might die… why were they so pissed at me?

It was only later when my parents approached the parents of the boy who hit me that I was able to talk to my friends again. With all of them present, I finally apologized. My parents didn’t understand what was going on, why they all hated me. They barely understood was a roleplaying game was, let alone why we got so emotional about it. But after that apology, we talked a little while. And we all agreed we should try the adventure again with the same characters. We’d tackle this thing and defeat it.

They played through it. After four weeks of sessions, they defeated the lich as the center of the tomb and got away with all the treasure. And now I’m going to tell you a secret that I never told any of them.

I cheated the whole way through.

I did everything in my power to protect their characters from the tomb. I made up saving throws for stuff that was instant kills. I dropped them hints. I even made up a bit that isn’t in the adventure: writing on the walls from previous adventurers, telling my group, “This is how we beat this trap.”

I had never modified an adventure before. Tomb of Horrors was the one that showed me how. I even invented Luck Points for my players, allowing them to spend a point if they missed a roll so they could try again. Much later, I would see similar mechanics in other games and I smiled.

Someone else must have run Tomb of Horrors, too.

The adventure completely transformed me as a GM. It made me re-think my role with the players. Running the game with the intention of looking out for them was so much fun… much more fun than I’d ever had before.

As we look back at our lives, we see patterns and chapters. Tomb of Horrors was an important moment in my life, both as a GM, a game designer and as a friend.

And it took the Worst Adventure Ever Written to make me understand that.

Coda

Much later in life, I met the author of that adventure. Gary and I were on a game design panel together. I said something I don’t quite remember and he called me a “wanna be community theater actor.” I wanted to tell him how his adventure nearly lost me every friend I had when I was twelve. Didn’t seem appropriate at the time.

But I also learned that Gary’s intention in creating that adventure was to kill off powerful characters. To teach players a lesson and put them in their place.

And I remembered being twelve years old, seeing my role as the GM in that light. “This is my world,” I thought. “And I can take you out of it any time I want.”

Fast forward even more years. I’m at a convention, sitting alone in a room, having a quiet moment to myself. A guy walks in, asks me, “I’m sorry. Am I in the wrong room?”

“Nah,” I told him. “This room was empty so I was using it.” I started packing up my stuff. “You’re in the right place.”

He smiled and told me, “I’m running Tomb of Horrors.” He said it was a gleam in his eye. “I converted it to 5th Edition. Wanna play?”

“I really shouldn’t,” I told him. “I’ve run it before. I know all the traps and stuff.”

He said, “Oh, that’s okay!” Then, he told me, “If you don’t help them out at all, it should be fine.”

I paused. Ran my tongue over my teeth. It’s a habit I have when I’m thinking. Then, I said, “Okay. Here’s the deal. I play a thief. I’ll specialize in finding traps. I won’t say a word about anything unless I find a trap, then I’ll tell them how the trap works. How does that sound?”

He agreed. I made up my standard thief character (the kid from the tavern) and the other players joined us. The GM had characters ready for them and handed them out. He explained my unique position and gave each of them 70,000 gold pieces to buy magic items and equipment.

I said, “Wait a second. Seventy thousand?“

The GM nodded. “That’s right.”

“One gold piece feeds a family of four for a year and each of us has seventy thousand gold pieces?“

He nodded again. “Yup.”

I told the other players, “Fuck this dungeon. Let’s go home. Live like kings. We don’t need to go in there. We each have seventy thousand gold pieces. Let’s buy a tavern… fuck that… let’s buy a city and be done with it.”

To their credit, the players considered that notion for a moment… then agreed they wanted to play the adventure.

“Okay,” I said. And bought the one and only magic item I wanted.

The adventure began. We found the first entrance.

“I roll for traps,” I said. And succeeded. I then told the rest of the players this is a death trap. If we walk down the corridor, we’ll step on a click plate (TM Grimtooth) and set off the ceiling falling on us and killing us.”

The rest of the players agreed to not go down that corridor. We then approached the second corridor.

“I check for traps,” I said and succeeded. I then told the rest of the players this is a death trap. If we walk down that corridor and try to open one of the two doors, a stone wall drops down, trapping us in. The walls then collapse on us, crushing us. We shouldn’t go in there.”

The rest of the players agreed to not go down that corridor. We then approached the third corridor.

We started walking down the corridor with me checking for traps every ten feet. I didn’t tell them about the secret passage at the bottom of the pit at the very beginning that allows you to skip a third of the dungeon because it isn’t a trap, but it’s there anyway, and you should find it and save yourself the trouble of trudging through a third of this worthless, piece of shit adventure.

When we got to the end of the corridor, we encountered the green devil face. With a mouth just big enough to fit inside.

The GM looked at me. I said nothing. After all, it’s not a trap. The green demon face is just a sphere of annihilation. I can’t check for spheres of annihilation, I can only check for traps.

The players started debating whether or not to get in. That’s when I spoke up.

“If you do,” I said, “you should leave all your stuff behind. After all, if something happens to you, we’ll need it to get through the rest of the dungeon.”

The player agreed and dropped off his pack. Then, he climbed into the mouth and vanished.

The other players looked at me. I shrugged. I said nothing.

Another player said, “Maybe I should go after him.” I gave them the same warning. They agreed, left their stuff behind, got into the demon mouth and vanished.

The third player asked me, “Should I get in, too?” I shrugged and said nothing.

So, the third player just climbed in—without leaving behind their stuff—and vanished.

I looked at the GM and said, “Do you want to tell them or should I?”

The GM grinned and told them, “All your characters are dead.”

I nodded and said, “I pick up the stuff they left behind, throw it in my bag of holding (the only magic item I bought), go home, sell all their stuff and retire. Fuck this dungeon.”

I dropped my d20 like a mic and left the room.

Because I’m a wanna be community theater actor. And that’s how we fuckin’ roll.

(dedicated to jim pinto and Jesse Heinig)

___

PS: I’m adding this a few hours after I wrote it, but it’s important for you to know. If you do finish the adventure, to prove the whole thing is nothing more than a way for a sadistic prick to get his jollies off, as a final “FU” from Gary, the treasure in the lich’s tomb is cursed. Just thought you should know.

This, right here, is a symbol. A personal symbol of mine. It represents all the wrong, backward thinking that people have about being a GM. I first encountered it in the early ’80’s when I was a player and not a GM. I didn’t have the actual adventure, rather, I heard about it from someone else.

This, right here, is a symbol. A personal symbol of mine. It represents all the wrong, backward thinking that people have about being a GM. I first encountered it in the early ’80’s when I was a player and not a GM. I didn’t have the actual adventure, rather, I heard about it from someone else.