I had a lot of trouble writing this. Five drafts.

There are many lies in the world, and so few hold any truth.

This lie is true

For it is true there was a time when our world was newly born and the Sun was red and rain was black and the Moon shone with a golden darkness.

And it is true that humanity fell from Heaven, but not the Heaven of any God we know.

Wary and wise are those who keep their minds ignorant of these truths, for those few who learn of how the world was, they pine for it like the kiss of a lost lover.

Night of golden moonlight.

And storms of black rain.

— The Book of Whispered Psalms

Sidebar

Her dreams were hungry, eating away her days.

Her sweat-soaked sheets clung to her skin, her bones so heavy, her muscles so weak. Even the noonday sun was dim in her eyes. Solace was upon her and all she could do was think back. Think back to her truest love and her truest enemy.

And, of course, he was the same man…

—from The Great and Terrible Life of Shara Yvarai

This is a Roleplaying Game

Hi there. My name is John and this is my roleplaying game.

Houses of the Blooded is a roleplaying game about tragedy. In it, you play a noble—one of “the blooded”—from a great and powerful household of nobles. You have lands and vassals and incredible power. But you are also hindered by your own passions and desires. You are the source of your own downfall. You will not play a single character, but an entire line of nobles, going down the ages, inheriting your ancestor’s strengths and weaknesses, living in a world that looks like a bastard child of Tanith Lee and Niccolo Machiavelli.

You probably know what a roleplaying game is: a game where you sit down with your friends with paper, pencils and dice with the intention of making up stories. You’ve probably played a roleplaying game before, even if it is one of those MMORPGs (Mighty Morphin’ Roleplaying Games).

You need at least two people to play the game, but you can have more. Most groups feel comfortable with four to six players. Every player takes on the role of a character except for one particular player—the Game Master. The Game Master (GM) has special duties in the game: he portrays characters not assigned to the players.

As a group, the players tell stories about their characters. Whenever those characters take risky actions, the players roll dice to determine the outcome. The higher you roll, the better. The GM rolls for characters not controlled by the players and makes decisions outside the players’ perview.

This is how roleplaying games work. But this roleplaying game is a little different than most. If you’ve never played a roleplaying game before, you won’t notice these differences at all. If you are an experienced gamer, these differences may knock you a little off-balance. But don’t worry: we’ve still got all the trappings you are used to. The game still operates under the basic premise of a group of players with one Game Master telling stories about their characters, rolling dice to determine the outcome of uncertain or risky decisions. But we have a couple of twists you should be aware of before we go any further.

The Big Differences

There are three big things in this book that make it different from most roleplaying games. I’ll put these right up front, right at the beginning of the book, so you’ll know about them in advance.

Time

If you’ve ever played a roleplaying game before, you know that characters always seem to get better. As they move through their lives, experience points always add to the character’s abilities. Regardless of how old they look, all roleplaying game characters seem to be an eternal and everlasting twenty-five years old.

Not so here.

Characters in this game begin young. Perhaps sixteen to nineteen. As the game progresses, they age. As they grow older, they learn new skills and discover new talents. As they grow older, however, age creeps up on them like an inevitable shadow. You can’t escape it. Its always around the corner.

This game is not about a constant push upward toward perfection. It is about doing everything you can in the time you have. There’s a clock on your character, constantly ticking. That hour hand always moving toward midnight.

It is always later than you think.

Success and Failure

In most roleplaying games, when you roll dice, a success means the Game Master tells you how your character succeeded. If you fail, the Game Master tells you how your character fails.

Not so here.

In this game, if you succeed on a roll, you get to narrate the outcome of your character’s action. If you fail on a roll, the Game Master narrates the outcome of your action.

It’s not at all different from a standard RPG. The only twist here is that everyone gets a chance to be the Game Master. To be the author of their own destiny.

Tragedy

There are all kinds of roleplaying games. Horror, fantasy, science fiction. But no matter the genre, there is one literary element that is almost never employed. That element of tragedy.

Houses of the Blooded is a game about tragedy. Now, most folks think tragedy means “when something awful happens.” That’s not what we’re talking about here. What we’re talking about is when the main character makes a terrible but well-informed choice. A choice the audience can clearly see as misguided, but because of his own circumstances, the hero cannot. As far as the hero can tell, his decision is the best decision to make, but because the audience has more access to information, they can see his choice will lead to his own downfall.

We hope the hero will recognize his mistake in time, but we know he will not. We hope for a happy ending, and the author may even give us hints that such an ending is possible, but we know in our heart that the end is inevitable.

This can only end in tears and blood.

But exactly who are the main characters of this collective work? An ancient and nearly forgotten people who called themselves “the ven.”

This is Not a Work of Fiction

About a decade ago, I learned about the ven. A pre-Atlantian people mentioned in texts such as the Book of Mu and the Voynich Manuscript, the ven were a passionate people, obsessed with etiquette, beauty and art. And revenge. Always revenge.

When my own research began, we knew almost nothing about them. No primary sources. The secondary sources were suspect at best, written almost entirely in Greek. The translations from those documents dated back to the late 1800’s. Needless to say, the “scholars” of that time took many liberties with the Greek translations, and the Greeks probably took many liberties with the primary sources.

But in 2002, a breakthrough. Discovered in a cave just south of Damascus, a small bundle of papers gave us our first primary sources.

The true voice of the ven.

A year passed before the first translations were released to the public, giving us our first look at the convoluted and trap-laden language. Since then, four of the documents have been released along with translations. An exciting time for ven scholarship.

Little Games

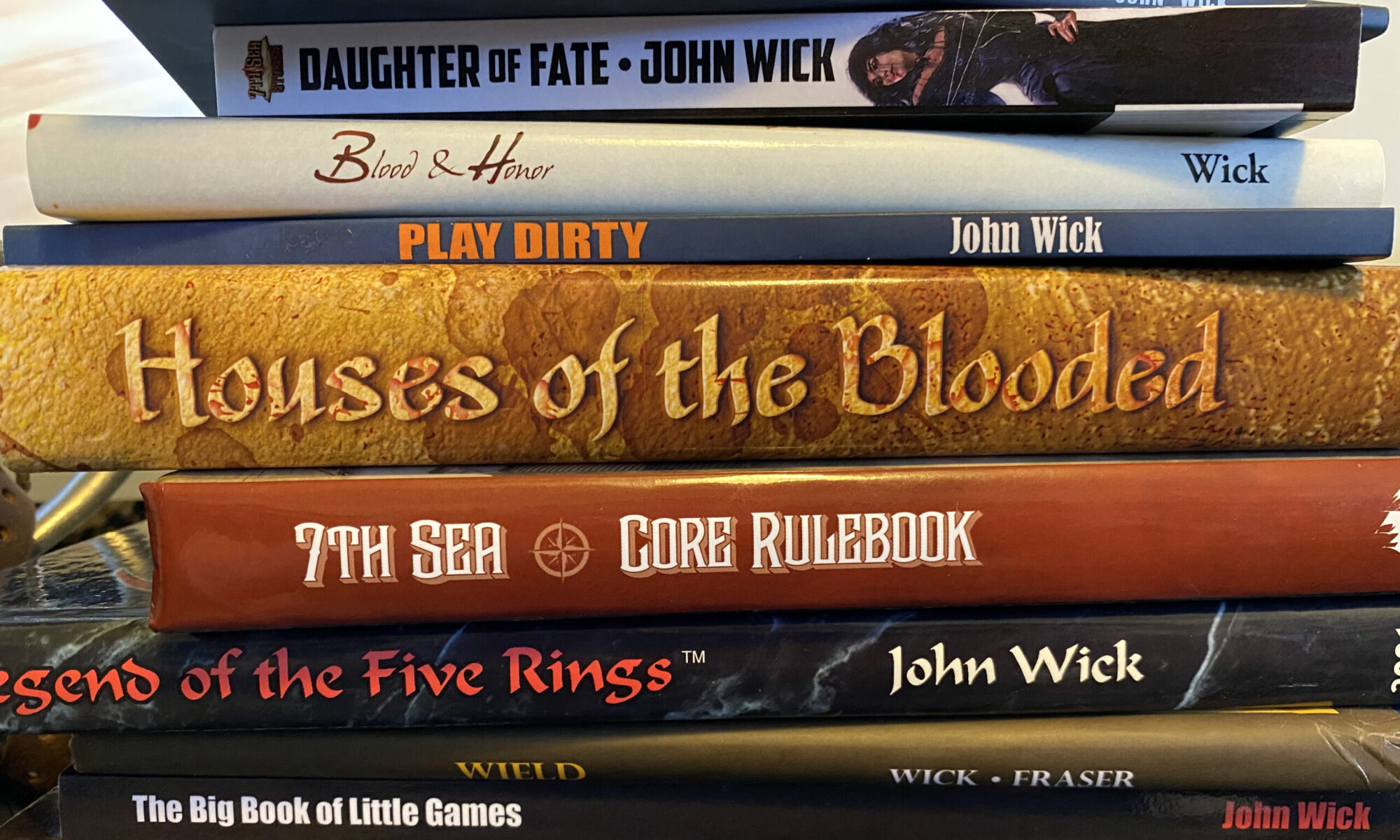

Meanwhile, as my research crept along, I was publishing little games for a publishing house I owned with my business partner, Jared Sorensen. We called it “The Wicked Dead Brewing Company.” We published little roleplaying games. Books no bigger than 100 pages (with one notable exception), focused themes and short-term play. All of these were very small compared to work I’d done on “big games” like Legend of the Five Rings and 7th Sea. And while my friends all enjoyed my little games, it was my friend Rob who voiced their collective desire.

“John, you should write a Big Game again.”

By Big Game, they meant something that could be played over a long period of time. A campaign game.

They kept bothering me and bothering me, and soon enough, I started to feel the urge to do just that. Design a Big Game.

And so, another dive into the pool.

Of course, when you dive into that pool, you really don’t have any idea if there’s any water down there. You just dive in and hope.

As it turned out, there wasn’t any water, but the ven were there to catch me.

Jared’s Big Three Questions

When approaching any game, I always keep these three questions close at hand. They help me keep focus on my work and re-direct me to my goals when I get lost. I also use them to help explain my game to others.

So, let’s ask those three questions right now.

What is My Game About?

This game is about tragedy. Specifically, the kind of tragedy found in the literature of the ven. It is about their style of storytelling, their culture, their obsession with romance and revenge.

In it, you take on the roles of ven nobles struggling to survive in a deadly and duplicitous culture.

But you won’t just play a single character. You have the opportunity to play many. Your noble will grow older as the years pass, transforming from a young noble to an adult, and then finally, to an ancient aristocrat looking for an heir. You may choose to play that heir, or you may choose to play another character. You can also take the roles of your noble’s various vassals. Master spies, valets and maids, roadmen, masters of the sword: these are all characters that fill the pages of ven pillowbooks and populate the stages of the theater and the opera.

More than that, though, this game is about passion and the price it carries; the implicit moral behind all ven literature.

How Does My Game Do That?

My game creates a sense of ven tragedy by embracing their culture and mindset like a knife through the heart. Right up to the hilt.

The game takes the six most prominent ven Virtues (Strength, Cunning, Wisdom, Martial Prowess, Beauty, and Courage) and makes mechanics out of them. Every strength on your character’s sheet is also a weakness: a vulnerability that can be taken advantage of by enemies. I have rules for trust, rules for betrayal, rules for love and rules for revenge.

In short, everything the ven portray as important in their own literature, I’ve made a mechanic in the game.

What Behaviors Does My Game Reward and Punish?

My game rewards players for acting like the characters from ven literature. Passionate but short-sighted. Powerful but vulnerable. Loyal but treacherous. The players are rewarded with “style points.” These points allow them to use mechanics on their character sheet that make their characters more powerful, but they get these points by making decisions that make their character more vulnerable.

The Eastwood Defense

There are precious few ven scholars in the world, but I have a feeling most of them will find a great deal of problems with some of the liberties I’ve taken in this book. Just in case they are reading, I want to make it clear that I’m taking The Eastwood Defense.

Clint Eastwood once said he wasn’t interested in “historical” movies as he was in making a film feel “authentic.” I like that sentiment, and when I wrote a game about samurai in Legend of the Five Rings, I stole it. Later, when I wrote 7th Sea—a game about Restoration era swashbuckling—I stole it again.

When I first approached the ven, I did so as I first approached the Japanese and European swashbucklers: I began by studying their language. I believe a culture’s language is the key to understanding that culture. I mean, when studying Eskimos and the world around them, it’s easy to see why they have so many different words for “snow.” For the ven, the most revealing element of their language was the fact they use the same word for “love” and “revenge.” Just a slightly different shift of accent on syllables.

Houses bears another similarity to my other big games. Like L5R and 7th Sea, this is not a historical game. L5R portrayed samurai culture in a romanticized light. 7th Sea did the same thing for 17th century Europe. But neither game was really about portraying historically accurate samurai or swashbucklers: both games were about portraying the literature of those cultures. The same can be said about Houses of the Blooded.

This is a romanticized version of the ven. It should not be considered anything near a historical document. In fact, I’ve done my best to pretty up the ugliest elements of ven culture while maintaining a sense of authenticity. It’s been a troublesome juggling act. A good example of an issue I’ve dodged is how ven culture treats the fairer sex. At their best, the ven treated women as second-hand citizens. At worst, as property. I’ve elevated the role of ven women to be as equals, as per the literature of the time. Not out of any sense of political correctness, but because playing a second-hand citizen just isn’t fun for most players. Of course, if you’d like to play a character who is property… well, maybe I’ll include that in a supplement.

So, again, in the tradition of L5R and 7th Sea, Houses is not meant to be a “historical game,” but rather, a game that authentically recreates the stories presented in ven literature.

Pillow Books, Plays and Opera

We have three sources of ven literature: pillow books, plays, and opera.

Ven pillow books (ushavana: “book for the bed”) were written for women. Romance novels. Romance novels with blood. Scandalous things, they drew characters larger than life, performing daring and dangerous acts. The most fascinating part of pillow book lore is the ongoing assumption that the books—almost all written under pseudonyms—were written by ven nobility, based loosely on their actual lives.

The most famous pillow book series centered on the character Shara Yvarai. The hub of a long series of fortunes and misfortunes, Shara’s story became a kind of prototype for others. The anonymous author, presumed to be a woman named Asara, was a maid to one of the most scandalous women in Shanri. Unfortunately, we do not have the true name of Asara’s mistress, but we do have a majority of the series. I’ve drawn heavily from this particular series for examples and illustrations in this book.

An escape from their lives, pillow books were all the rage during the time I’m drawing from here. Of all their literature and history, pillow books are the largest source of information regarding the ven.

Ven theater, on the other hand, was a bloody affair, filled with revenge, violence, and carnage. Written for the masses, its powerful themes were considered too passionate by the nobility… but that did not stop them from donning a slumming cloak and sitting in the darkest corners of the theater to enjoy the spectacular mess.

Opera, however, is the Great Alchemical Art. A demanding and exacting form, opera invokes theater, music, dance, painting, and all the Arts. With ancient characters written bigger than mountains, it is, without a doubt, the most powerful of all the ven Arts. Ven opera must be seen to be believed.

Theater, pillow books and opera. As I said, this book draws from ven literature rather than history. I’ve used scholarly sources to give certain ambiguous elements of the culture context, but in the end, this should not be considered an authoritative work. For readers more interested in historical documents, I refer you to the short bibliography at the end of this essay.

The Ven Writing Style

I should also warn any readers not familiar with the ven language about a few eccentricities.

I have on many occasions (semi-humorously) referred to myself as a “method writer.” I find adopting the philosophies of my subject matter helps me capture the essence of their spirit as I write. It was so with games such as Legend of the Five Rings, 7th Sea and Orkworld. Expect no different with the ven.

I have tried my best to adopt not only the philosophy of the ven, but in translating their texts, I have also made every attempt to stay true to their language. This will cause a few problems. To begin with, the ven had a very different attitude toward their language than most modern societies. For example, the ven language—yllanavana—has some rather lax rules regarding usage and grammar. The ven attitude toward language was, “If you can communicate meaning, your usage is correct.” This particular attitude drives most Western scholars mad. Often times, you will find them breaking the rules of usage for the purposes of effect. Single word sentences, fragments and other stylistic oddities are common.

Common.

The ven also employed repetition as emphasis as well as capitalization. The ven loved capitalizing Auspicious words. They did it time and time again.

And again.

And again.

As for the language itself, most scholars assume yllanavana was a kind of singsong, their prose reading like lyrics, almost like poetry. Every sentence an intentional act of Beauty.

I apologize in advance if my stylistic voice in this book escapes me from time to time. The ven viewed such writing as a Virtue. Such lack of discipline demonstrated the writer’s passion. Petty rules of grammar could not hold back the emotion in his heart. Pounding. Seeping into the words. Finding the reader. Reaching up through the page, grabbing him by the throat, shouting into his face.

Again, apologies in advance. And you have been warned.

Now, enough of my yappin’! Let’s boogie!

Bibliography

Alvarez, Anthony. “Love and Revenge in Ven Culture.” Academic Journal of Quasi-History & Metaphysics. 2000. Volume 8, pp. 277-288.

Anonymous. The Sword: Complete. Translated by Berek, Jeremiah. Bakersfield Publishing Inc. 1901.

Armitage, Henry. Thoughts on Lessons: Fragments Translated with Annotations. Private Publication. 1927.

Asara. The Great and Terrible Life of Shara Yvarai, Volumes 1-5. Author’s private collection. Publication date unknown.

Avalon, Elaine. Blood Opera: A Tradition of Tragedy. November Press. 1967.

Black, Jacob. Ven Magic and Mysticism. Private Publication. 1872.

Carter, J. Pre-Atlantean Cultures. Vincenzi Press. 1922.

Dare, Virginia.

Fledderjon, Marcus. Virtues: The Complete Yvarai Text. Dancing Goblin Press. 1899.

Pugg, O. “Troubles in Translating Ven Texts.” Mu Magazine. May 18, 1992.

Shosuro, K. “The Role of Women in Ven Pillow Books.”

Szasz, Roland. “Sex and Magick in the Ven Tradition.”

Wick, John. Enemy Gods. Wicked Dead Brewing Company. 2001.