Houses of the Blooded: The Recalcitrant Heart

We’ve talked about opera. Now, let’s talk about that “lesser” Art. The one the nobility ignore. The common man’s opera.

Let’s talk about theater.

Filthy. Uncouth. The crowd screaming at the actors, throwing biscuits and fruit. A mob, not an audience. And high above this mob, high above the rotten straw and the spilled beer, are the cloaked boxes where hooded men and women watch. And smile.

No self-respecting man or woman of the Senate would ever be caught dead in a theater.

The theater is the common man’s opera, but ven nobility have discovered a Truth about theater. It is where actors embrace what the ven call “the recalcitrant heart.” Plays are written by authors, but the actors are not expected to memorize the lines. Instead, they learn the part well enough to bring the true emotion of the character to the stage. Summoning the spirit of the character. Letting him enter you. Letting him speak for you. Letting him guide your hand, your tongue, your heart.

Often, the character cannot keep with the script. His own desires, his own passions. They guide him. Not the passions or desires of another. Actors on the stage know this and embrace it like a dagger through the chest. They allow the character to take over, to take the lead. Some ven claim to see a different person when an actor takes the stage. Possessed by the character, he is a different person.

Dangerous magic. Peasant magic. Not the forbidden sorcery. Something different all together.

This is the holy rule of the theater. Allowing the character to take the stage.

No set number of plots or characters. No rules. But the audience is always watching. The audience is unforgiving. They came to see that magic. Possession. And they can tell when an actor has it and when an actor does not.

Ithuna. “Faker.”

Cabbages and biscuits.

In the theater, the audience cheers, the audience cries. They boo and jeer. They grow deadly silent. Waiting.

When the ven go to the opera, they know what to expect. No-one knows what to expect in the theater. Anything could happen. Love. Revenge. Murder.

And an actor cannot be held responsible for what his character may do.

Love. Revenge. Murder.

The theater.

Houses of the Blooded: Blood Opera (Revised)

An expanded and revised entry on blood opera. Enjoy

The high alchemical Art, incorporating all other Arts. Drama. Music. Architecture. Dance.

And, of course, love and revenge.

Ven opera (the actual ven word best translates as “The Art that encompasses all other Arts”) is full of spectacle. Jim Steinman meets John Woo. The thunder of the music cracking the plaster in the walls. Actors bursting their throats, their eyes full of rage and tears. Musicians in the pit, playing furious anger and beatific joy. Choirs chanting choruses over and over and over.

There is no word in the ven language for “understatement.”

Like everything else, the ven are obsessed with the proper presentation of opera. So much so that they only recognize six plots as appropriate to the stage. This requires a bit of explanation.

Think for a moment about our own King Arthur. Just saying the name summons images and names. Camelot, Gwenevere, Lancelot, Excallibur, Mordred, Merlin, Morgana, love, loyalty and betrayal. Arthur’s story has been told thousands of times in thousands of different ways, but the key characters and elements remain. And though storytellers have taken liberty with Arthur’s tale, we accept those liberties so long as the truth of the story remains intact and honored.

When Arthur’s story goes too far from what we expect, we feel betrayed. Not an emotion easily explained. An instinct. An understanding. Almost as if we have to protect the story in some way.

So are the ven and their opera.

Only seven stories are worthy of the stage. The ven recognize these stories from the character’s names. Just as we would know the plot the moment Hamlet’s name was mentioned. Or Odysseus. Or even James Bond. And while the plot may weave differently, certain key elements remain. Secondary characters come and go, but the lynchpin personnae remain.

Authors and composers work to re-tell these six tales with different voices, using each to communicate a new moral, a new truth. Just as Arthur’s tale can communicate the conflict of true love and duty, so can it tell the conflict of Christian against pagan. So can it tell the tale of Britain’s natives against her invaders. Just a tweak of the pen and a familiar tale delivers a different message.

So are the ven and their opera.

Lesser tales are delegated to playhouses and street theater. But not the opera house. Not that great and sacred place. Seven stories. Only seven.

And there is only one ending. Blood.

The High Alchemical Art, combining all the disciplines into a transcendent experience. Music. Poetry. Drama. Transforming the opera house into the place of imagination, where heroes and stories wait to be discovered.

This time in ven history is the golden age of opera. Unfortunately, we have precious few texts from this time (because of the Dire Times that would soon follow), only a handful of the manuscripts from these amazing works. Most of the documents we do have are severely damaged, giving us only a glimpse of the work.

WORKS AND FOOLS

“Fate and Chance are the undoing of us all.”

— from the libretto of Ufaltir by Rhondir Yvarai

The ven were very specific about their opera. So much so they recognized only seven operas as “official.” All other operas were lesser works, not truly inspired, not Art.

These seven operas, or Great Works, may be called tragedies if there were not so much joy in the libretto and orchestration. It seems the ven found great joy in blood and death and calamity. But ven tragedy is very specific, and since the word has taken on so many different definitions in our own culture, I’ll take a moment to specify what the ven meant by the word.

For the ven, tragedy has specific necessary elements. To begin with, the ending must include the death or undoing of the hero. Also, the hero of the tale must be responsible for his own undoing. This may be a slight at the beginning of the opera that triggers a series of events eventually leading to his demise or it could be a deliberate action, a decision that destroys him. In short, “accident” does not belong in ven tragedy. Chance and Fate work against him, his end always inevitable, but his end is due to his own shortcomings. His own lack of Virtue.

The Great Works are based on seven characters that appear in all operas. Each opera focuses on one of these seven characters, otherwise known as “the Seven Fools.” These seven characters alternate as the main character. While the appearance of the characters may alter—the genders, the names, the relationships—the Seven Fools are consistent through all the Works.

Like I said, the Seven Fools have been portrayed as both genders, but the role itself is always referred to as gender specific. For example, there have been both male and female characters who fit the role of “the Rake,” but because he first appeared as male, that role is always referred to in the male gender.

The Seven Fools are: the Actress, the Dowager Duchess, the Husband, the Rake, the Swordsman, the Wife and the Wise Man.

THE ACTRESS

The character known as “the Actress” rises up through ven society through some sort of Art. She comes from humble beginnings, but convinced by the praise of others, she loses sight of those beginnings.

The first Actress was Q’vanna Yvarai from the opera of the same name. A common theater actress she took to the stage only to bring enough coin to feed her aging and crippled father. She was discovered by a slumming lord (the Rake), and enchanted by her beauty and talent, he trained her in the ways of the Great Art, bringing her to Shanri’s most magnificent opera houses. But her pride blinded her. She abandoned her lover, destroyed her reputation with scandal, and ends her life with suicide. The variations on the Actress are many, but nearly all of them end with the ambitious youth taking her own life.

THE DOWAGER DUCHESS

The Dowager Duchess is a woman (or man) who is advanced in age, but refuses to acknowledge the inevitable grasp of Solace. She acts like a young woman until the cruel truth of the world comes knocking on her door, and finding her unprepared, she faces death, losing the sleep of Solace forever.

The first Dowager Duchess was Lady Peacock, a very popular character in ven literature. A tragedy in every sense of the word, the opera begins as pure farce, a comical satire of ven culture’s hypocrisies and double-standards. She spends so much time with banter, she never takes advantage of opportunities to say something meaningful, to say and do the things she should before Solace takes her away. The opera ends with the Duchess’s inevitable passage into Solace, surrounded by friends and family, unable to speak, weeping, longing for just one more minute so she can say what needs to be said, to alter a tragedy of her own making. Of course, Solace claims her voice and all she can do is watch. The theme of the opera is plain: the end is sooner than you think.

THE HUSBAND

The Husband is often portrayed as the neglectful spouse. He is often male, although he has been portrayed as female on rare occasions (and equally rare success). His undoing is underestimating his wife’s (or husband’s) desires for independence and happiness.

The first appearance of the Husband occurs in the opera Darby’s Pride. Darby Steele spends all his time securing his lands, building a great castle, and ruining his enemies. All the while, his wife’s own desires are neglected. The opera portrays her as devoted, loving, and willing to sacrifice for security. She gives away a chance at true love with a less ambitious baron for Darby, and slowly regretting her decision. At the end of the opera, Darby discovers her in the arms (and bed) of another man. He kills them both and burns down his castle, racing into the wilderness, completely mad.

THE RAKE

The Rake is unmarried, either male or female, looking to rise through society through romantic conquests. His undoing is his own shallow heart and misunderstanding of the sacredness of love.

Of all the Great Works, it seems the ven were most liberal with the Rake. Identified by his name—a play on Sh’van, the original Rake—each opera seems to be a different argument about the true nature of love. He may be young, he may be old, he may even be a woman, but he always faces the conflict of love versus duty. In the original opera, he is a young noble seeking to restore the lands of his wounded father. Unable to maintain the lands himself, the Rake seeks allies by seducing wives of other nobles, secretly making alliances behind their backs. But true love calls in the form of a family friend, thought long lost, and everything the Rake has worked to accomplish comes crumbling to the ground when he must choose between the woman he loves and a woman who can save his lands. How the Rake chooses changes with each tale, but it always ends with a betrayal and tragedy.

THE SWORDSMAN

His prowess unmatched, he walks the streets of Shanri unafraid, taking all challenges. This is Cyrvanto, the Swordsman. Arrogant, and proud of it, he refuses apology, demanding the sword answer all threats to his honor. All of which, of course, lead to his undoing.

In Cyrvanto, we see the swordsman: a man of courage, wit, and cruelty. He has no mercy for those who would oppose him, no mercy for those who taunt him, no mercy for those who question his honor. But then, he meets his match: a woman of equal skill, of equal wit, of equal cruelty. It is she who undoes him. Looking to make a reputation for herself, she wins his favor and eventually his heart. Then, using the knowledge and trust she gained, she challenges him to a duel. Unable to kill the one thing he learned to love in all his life, her sword finds his heart, ending his life and the opera.

THE WIFE

The Wife is demanding, selfish and proud; the things that allowed her to reach the pinnacle of society. Unfortunately, these same qualities are her undoing.

The story of Benejitrix is a familiar one to the ven, found in the opera, One Stitch Too Many. Benejitrix is a beautiful woman married to a scoundrel of a man. Marrying for his lands, she hopes to end his life prematurely, claiming his lands as her own. Her stepson, equally ambitious, plots with his mother. (Many versions play up the sexual implications only hinted at in the first production.) Her plans are thwarted, however, by her own ambition and the betrayal of her stepson, leaving her scandalized and alone.

THE WISE MAN

The character of the Wise Man is one of the least popular subjects in ven opera. Of all the Fools, his tragedy seems the most difficult to make compelling to a ven audience. Most Artists see the Wise Man as a challenge, attempting to make this character into high Art. Most fail. Neglected for decades, it seemed the Seventh Fool would fall from grace… until one Artist succeeded to such a degree, all his following work was said to pale in comparison.

Entitled Bjornae, this particular Wise Man was not wise at all. Instead, he was a simple soldier thrown into circumstances beyond his control. On the verge of an attack from a legion of swordsmen, the desperate Count turned to a ragged soldier, seeking any advice at all. The soldier, completely over his head, gave the Count his advice. “Swimming requires stamina,” he said. This nonsensical statement was seen as deeply profound by the Count, who used it in a brilliant maneuver to defeat his enemies. After that moment, Bjornae becomes the Count’s advisor, giving him nonsensical advice the Count interprets as deeply insightful. The tragedy of the tale, of course, does not fall on the Wise Man, but on those who think themselves wise. Yvala Mrr wrote the opera, a daring shift from paradigm that stuck in ven consciousness for generations.

THE SERVANTS

Another omnipresent element of ven opera is the presence of “the Servants.” Two Servants, always named Ythala (a woman) and Talsho (a man), appear in all variations, acting as a kind of Greek chorus, giving exposition to the audience with their gossip.

Traditionally, the servants have the last word, giving the moral of the opera to the audience, although more bold artists use the Servants to comment on the moral. Dangerous. But then again, true Art is always dangerous.

The Adventures of Bear

When I started working at Perot Systems, I discovered the Lead Trainer had a small teddy bear on her desk.

“Oh, that’s Bear,” she told me. “He goes through all sorts of torture.”

It seems our delightful Lead Trainer brought Bear into work one day after her boyfriend won him in a machine or she acquired him in some other mundane manner–fully unaware of Bear’s symbolic importance. As soon as she brought him in, strange things started happening.

She’d arrive in the morning to find Bear with a broken arm. Or hanging from a cord by his neck. Or squashed under a heavy weight.

“He goes through a lot,” she told me.

I said, “But he always survives. That’s because Bear can’t die. He goes into the cave in winter to wrestle the God of Death and emerges in the Spring.”

“Oh,” she said, smiling. “That’s neat. I never thought of it that way before.”

Having learned how to revere Bear, I’ve done my best to lead the “Pro-Bear Lobby” at work. She showed up one morning and he had a jar of honey along with a note. “I found the honey!” He also found the fish. A bag of Goldfish crackers, to be exact.

However, Bear disappeared a few days ago. Nobody seems to know where he went. He’s been gone since Wednesday, although I suspect he may show up on Monday morning. And he may show up with a disc of photos, chronicling his adventures.

(I should note that “Bear’s Adventures” are largely due to the ingenuity of Jessie Foster. Go Jessie.)

This is Bear at the cafeteria, getting a little something to eat before his grand day out.

Here we find Bear with an assortment of new friends. Bears can always use a few new friends.

Checking out Phoenix from a Bear’s eye view.

And finally, Bear in his natural habitat.

Sans Caffeine

What happens when I cut caffeine out of my diet?

I get headaches during the day and insomnia at night, that’s what.

I quit after I read the specific chemical compounds in sodas have been directly linked to neurological problems. I saw it two weeks ago and I can’t find the link.

God, I want a Coke.

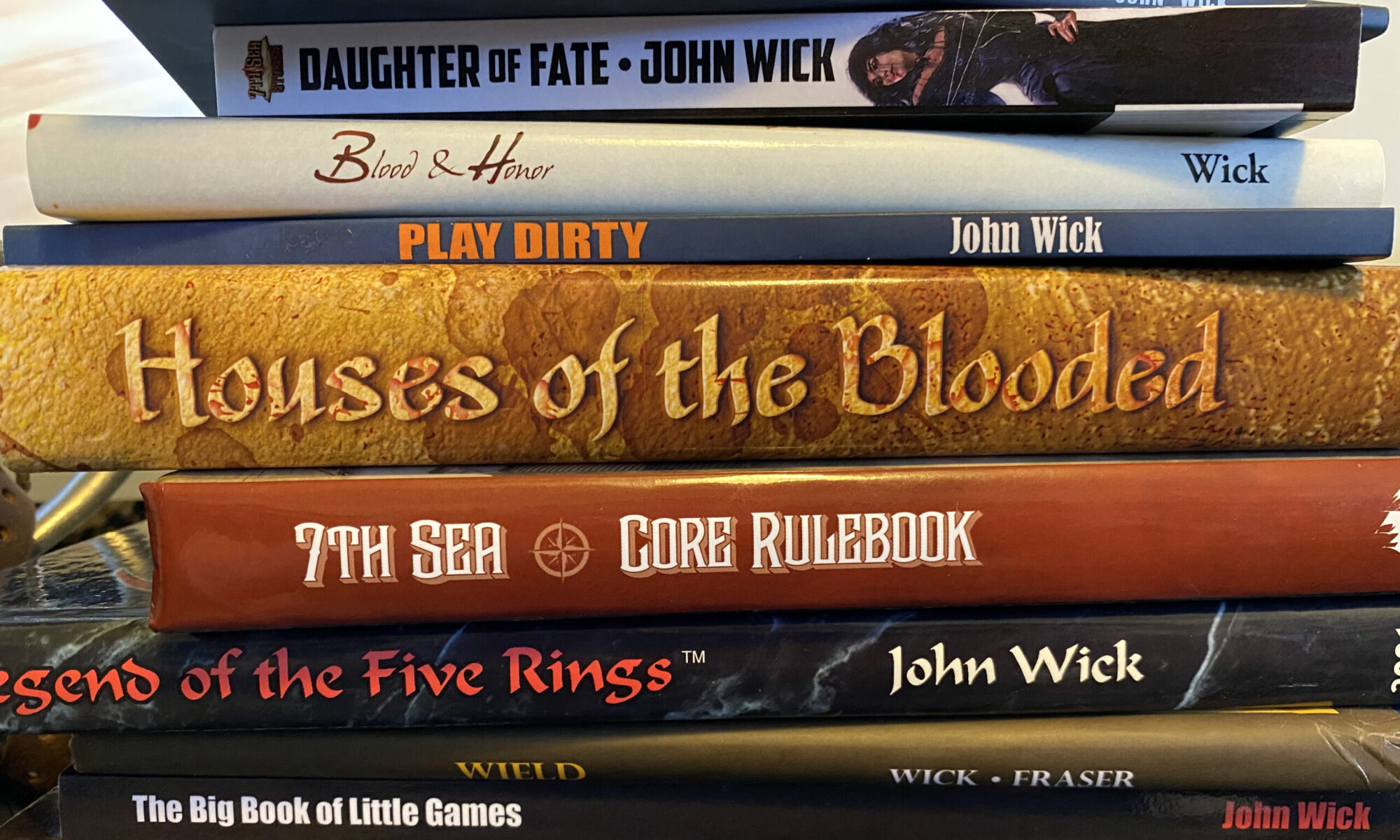

Houses of the Blooded & Play Dirty: The Ultimate Showdown!

So, I’m including Player and Game Master chapters for Houses of the Blooded and I realized what I had just written would have made a great Play Dirty chapter. Specifically, a follow-up on the “play dirty for players” chapter. That’s right, more goodies for you player-types.

Don’t worry, you don’t need to know anything about Houses to understand what’s going on in this chapter. There are a couple of references, but the idea is pretty universal.

So, for fans of that little firecracker, here’s 2700 words on The Morley-Wick Method of Roleplaying.

(a special tip of the hat to Sheldon who gave me Mamet and to Jared who taught me everyone can be the GM.)

Actually, Sheldon is an actor and a musician. He’s still a good friend of mine. And by “actor,” I mean real actor. Not us wanna-be community actors, no, my buddy Sheldon has skills.

So anyway, Sheldon and I used to go to LARPs. (That’s “live action roleplaying” for all you unsophisticated heathens.) A lot of LARPs. But Sheldon and I seemed to have a problem. We were driving home from a particularly boring LARP, complaining as we usually do. I don’t remember which of us suggested it, but one of us said, “Maybe we’re doing something wrong.”

But what could we be doing wrong? We had great characters. Characters with history. Deep history. Well-written and easy to work with. We were rich with potential. Untapped potential.

And yet, there we were. Bored out of our skulls. We’d interact with the other players, but only in a shallow way. There was just nothing to talk about.

And when we looked around, it seemed to us that the most successful players had the most shallow characters. That is, there really wasn’t anything to them. So, again, why were we having such a miserable time when those other folks were having so much success?

That was our first observation, but in fact, we were wrong. Our observation had betrayed us. It took deeper analysis to understand our problem. So, we sat at Norm’s (at 2:00 AM) and talked about it. Sheldon came up with the solution.

“We’re playing the wrong game,” he told me.

I grabbed the ketchup and Tabasco for my eggs. “What do you mean?”

“Our characters have deep secrets.”

“Yeah,” I said.

“That nobody knows but us.”

That made me pause. And think. “Yeah,” I said. Slowly.

We spent the rest of the night talking about the problem. It wasn’t a problem with the other players. They were playing the game correctly. The problem was with us.

I think Sheldon also nailed down the guy who could solve our problem. David Mamet. The director/screenwriter. His books and essays on “the method” approach to acting really inspired Sheldon, which in turn, inspired me. Using Mamet’s critiques, we came up with a solution to our problem.

From Mamet, to Sheldon, to me. To you.

What’s Wrong?

So, after that long introduction, let me explain what Sheldon and I were doing wrong and why it relates to David Mamet.

“The method” is an acting technique. Actors try replicating real life emotions, calling on sense memories from their own past similar to the emotions the character experiences. Method actors also create “rich interior landscapes.” That is, they create detailed histories for their characters. They know everything about their characters, so when a circumstance arises, they’ll know how their character would respond.

Rich interior landscapes.

Watching an actor on stage, watching him respond to something seemingly innocuous with a cryptic sigh or a mysterious glance or some other enigmatic gesture. The audience doesn’t know what it means, but obviously, the actor’s done his research. He’s done the work. He’s using the method.

Unfortunately, the audience doesn’t know what it means. The actor isn’t communicating anything to the audience.

In other words, he’s failing the entire purpose of acting. Communicating to the audience.

As gamers, we have a similar problem. We come up with elaborate and detailed backgrounds. Rich internal landscapes. And then, when we start playing, whole sessions go by without the other players having a single clue. Cooperative storytelling.

Characters have secrets. Sure they do. That’s fine. But authors use devices to give the audience clues as to why a character responds a certain way. We get to see that rich internal landscape. Even if a reaction is a mystery, we trust that somewhere down the line, the author will let us in on the secret. We’ll eventually understand all those cryptic sighs, mysterious glances and enigmatic gestures. Eventually.

But in roleplaying games, we keep secrets. We write the GM private notes. We take him aside for a whispered meeting. We keep that 24 page background to ourselves. Nobody else gets to see it. It’s ours and ours alone.

The method. Secrecy. Otherwise known as mental masturbation.

You are, quite literally, playing with yourself.

Nobody else is invited. Nobody else gets to know about your character’s past. That lost lover. That blood feud with your father. That secret conversation you had with your mother. Your childhood rivalry with your sister. Your secret marriage. That secret you’ve kept for twenty years and never told a soul.

All that rich background you’re selfishly keeping to yourself. That no other player will ever know about. It’s yours and yours alone. And you’re the only one who will ever enjoy it.

This is what’s wrong. We’ve got great characters and nobody knows but us. Why is that? Why do we feel we need to hide our characters’ secrets from the other players?

Well, most LARP settings are PVP (player vs. player), so we don’t want others to know our secrets. We assume the other players will take advantage of out-of-character information. And, sadly, we’re usually correct in this assumption. But at a table top game, surrounded by friends and people we trust, why do we still follow the same behavior?

Reflex perhaps. Maybe it’s just habit.

Well, let’s break that habit. Let’s get out of the “method” philosophy of character creation and play. Let’s try something different.

Let’s have open secrets.

A Novel Approach

Now, I should be up front about this. Many of these techniques are not new—I didn’t invent them—but putting them together in one set, with one philosophy guiding them, I think qualifies as “a new approach.”

I’ll take you through it, step-by-step. Read through them, adopt the steps you like, throw out the ones you don’t, come up with your own. After all, this whole chapter is about modifying things to your own group’s tastes. Step-by-step.

Character Background

One page.

That’s all you get. One page. I’ve provided a page for you at the end of the book for your character’s background. That’s all you get. Don’t try writing small or using a tiny font.

One page.

I know, you’ve got a lot to say about your character. This is what I call “Character Control Syndrome,” or “CCS.” You think this is the last time you’re going to have any control over your character, so you want to squeeze as much content and detail in there as possible.

Relax. Take deep breaths.

Just write one page. In fact, don’t even finish filling out the page. Leave a few details open. Figure out what you think is important, but leave the rest blank. Vague. Open. Let me tell you why.

I was playing a character once. A magic cop. I really didn’t have any idea about his past. I just kind of made him an arcane Columbo. But I bumped into a story involving a kidnapped girl. Something triggered in my head. I had no idea about my cop’s family. Wife, kids. No clue. I hadn’t really thought about it. But at that moment—that very moment—I knew he had a daughter. And he lost that daughter. I didn’t know how or why. I just knew it. I knew it.

That one little detail, a detail I didn’t know until I started playing, changed the entire course of the character’s past and future. Completely changed him. Turned him from an arcane Columbo into something much deeper. And, in a lot of ways, a lot scarier.

All because I had kept a detail open and filled it during play.

So, one page. That’s all you get. If that. You don’t need to know all the details before you roll dice. Some details—most, in fact—you can discover days, weeks, even months after the first session. You’ll bump into things that inspire you to fill in those blanks. Keep an eye out for even the tiniest details. After all, like grandma says, it’s the little things that make the soup.

External Exposition

Tony is a friend of mine. He has a style of play that’s always intrigued me. Specifically, he practices external exposition.

He doesn’t just tell you what his character is doing, he tells you why his character is doing that. Like an author, he gives you subtle clues. For example…

Tony’s playing RevQ’an Burghe, a minor Baron from the northern islands. He’s one of the many nobles at a party both of you decided to attend. As the GM, I ask Tony, “What are you doing?” This is his reply.

“I stand up,” he says. And he stands up. “And I walk across the room. My pace is slow. My head, hung low. My hand hangs on my sword pommel. Gripping it. Like I don’t know what to do with it. When I get to Baron Vaccon (that’s you, by the way), I hesitate. You can see there’s something in my eyes that tells you I don’t want to do what I’m about to do. And I think about the promise to Lady Shara I made. And the promise she made me. And then, I say, ‘Baron… I find myself in the position where I must challenge you to a duel.’”

Tony pantomimes all these behaviors. He pantomimes his hand on the sword. He walks across the room slowly. Uncertainty in his stride. And when he talks to you, his tone reflects the exposition he’s giving.

The exposition punctuates the action. Not only does he give you external clues, but he gives you internal clues as well. “I think about the promise…” He even gives a bit more information than he should. “And the promise she made to me.”

Tony leaves himself wide open when he plays. He exposes his character’s weaknesses, keeps no secrets. Why does Tony do this?

Because he knows his friends won’t take advantage of him and sabotage his fun. Besides, part of the fun is knowing other character’s weaknesses. And having other players know yours. We put weaknesses on our sheets because we want them exploited. We want to get hurt, get knocked down, get beaten within an inch of our lives. How can we come back from the bottom if we never even get knocked down?

You’re probably familiar with the term “Mary Sue character.” Over-idealized characters who never make a mistake, never flounder, never flub their lines. You see them all the time in fan fiction. You see them all the time in professional fiction, too.

You see them even more in roleplaying games. A lot more. Especially when you run con demos. Oh, Blessed Eris. Flashbacks. Flashbacks!

Excuse me for a moment…

It’s okay. I’m back.

One of the reasons I designed Houses with weaknesses was to avoid Mary Sue characters. The ven aren’t just bigger than humans in good ways, they’re bigger than us in every way. That means their flaws are bigger, too.

Now, if you play your character close to the chest, if you don’t let the other players see his foibles as well as his strengths, no-one will ever get to see that great background you developed or hear that inner monologue they’d usually get to hear if they were reading a book or watching TV.

Use external exposition. You don’t have to do it like Tony does. You can find your own way to do it. But do it. Let the other players in. Let them see the man behind the curtain. Armed with wagers, they’ll be more than happy to let your character live out that tired old Chinese cliché about “interesting times.”

And you’ll thank them for it.

No Passing Notes in Class

A lot of players like passing notes and having secret meetings with the GM. Especially in a game like this one where everyone has a secret to keep.

Here’s the news. That’s done.

It’s no fun to sit around while the GM goes off into another room with another player and has a private chat. For those of you who’ve done this (including in games I’ve run myself), I applaud your patience and your selflessness, but you don’t need to do it anymore.

Secret meetings get handled in front of other players. You got a note? Say it out loud.

Once again, we’re all grown-ups. We’re all friends. We all want to have a good time.

And nobody gives a single flaming turd about your rich internal landscape if they never get to see it. So, be a ven. You’ve got it. Flaunt it!

Share Plots

One of the side-benefits of being open about your character’s past is finding parallels with other characters.

You’ve got a vendetta? I’ve got a vendetta!

You’ve got a romance? I’ve got a romance!

You’ve got a hated uncle? I’ve got a favorite uncle! Maybe they’re the same!

The more connections with other characters you can make, the better. Giving you both something in common, something to talk about, something to commiserate about.

Trigger Plots

This takes a lot of trust. Use at your own risk.

The GM is a busy guy. He’s got five to six players to worry about, and sometimes, he just doesn’t have the time or focus to hit everybody every session. Sometimes, players get overlooked. Sad, but true.

With this little trick, you’ll never get overlooked.

As above, share your backgrounds with the other players. Send them all around the table. Everybody gets a peek. Look for trouble areas. You know, places where you could cause trouble if you were the GM.

Then, when you see an opportunity to do cause trouble, do it.

For example…

Shara has a problem with her father. All the players know this because they’ve read Shara’s background. They also know that she’s looking for the man who killed her mother. Armed with this knowledge, they start screwing with me.

They use wagers and style points to have Shara’s father come walking out into a party half-dressed and fully drunk. They use wagers and style points to have NPCs drop suspicious hints about secrets only Shara’s mother would know. And then there’s the kicker. One player uses style points and wagers to have Count Xanosh mention he has the missing pages from her mother’s diary.

Wagers and style points.

One more example. (Although, this one is kind of a cheat. I’ve changed the details a little bit for illustration purposes. I hope the people involved will forgive me.)

Meanwhile, on the other side of the table, there’s a young woman named Ro. She’s been playing a kind of dowager duchess in one of the playtest games and that character has a beloved servant: her frightened and fragile maid, Alice. Now, for a few months, Alice has been shivering and quaking and nervous around all the big, bad, violent beautiful noisy people. Alice doesn’t talk much, fetches tea and biscuits really well and stays out of the way even better.

But then she got caught in a little bit of trouble and someone used sorcery to force Alice to tell the truth. Someone asked her, “What have you been up to?”

And someone spent a style point and answered for poor, little Alice.

Pantomiming the whole scene, the player shows us what happens when Alice is asked the question.

Poor trembling little Alice suddenly straightens her back. Her face calms. Her breath shallows. Her eyes fill with confidence. And Ro’s little helpless maid, speaks in a deep voice she’s never used before.

“I’m a house assassin, spying on my lady, sending information to Lord So-and-So.”

The whole room was stunned. Now, that’s a typical revelation for a game like this, but what can make a revelation like that great is that it can come from the players.

The GM could have done all the stuff we’ve been talking about, but he’s just one guy. Plus, he’s got five other players to worry about. I’ve got six GMs now, each complicating my plotlines, making things more difficult for me.

Just the way I like it.

When other people know how to punch your buttons, they get pushed. And as bad as that might sound, it’s a lot better than getting overlooked by a busy GM.

Flashbacks

I also allow other players to trigger flashback scenes with style points. If another character does something odd, reacts in an unexpected way, or otherwise catches the players off-guard (even if it’s the player in control of the character), someone spends a style point and we’re off to a flashback sequence.

Each player can spend a style point to participate, playing a part in the flashback. The player with the spotlight can run the scene as the GM or let the GM do her own job or let another player be the GM for a while. We invent a scene, right there on the spot, with circumstances similar enough to the scene we were just playing, adding deeper meaning to the scene and the character.

But remember the Lost Rule. Don’t make the flashback more important than the current scene. Flashbacks provide additional flavor to current action. Flashbacks do not eclipse current action.

Of course, you could run an entire session as a flashback scene if it’s really important. An example of that may be Shara reading her mother’s missing diary pages, finally getting her hands on mom’s missing diary pages. Three degrees of cool here.

- First degree of cool: the GM tells me what they say. Eh.

- Second degree of cool: the GM makes the prop pages himself and gives them to me to read. That’s pretty hip.

- Third degree of cool. The group plays out the events in the pages with all of us discovering together what happened. Yeah, it’ll take me weeks to recover from that.

Remember, the ven go to eleven. Or, in this case, to the third degree.

Conclusion

Here’s the big lesson here. Keeping secrets is fun. Revelation is fun. Revealing a secret you’ve been keeping for months is a lot of fun. You don’t have to use all the techniques I’ve listed above, nor do you have to get rid of secrets. But keeping everything to yourself isn’t just selfish, it’s spoiling everyone’s fun. Including yours.

Ah, youth…

Houses of the Blooded: Revenge, Part 2

When a plot has been given poetry, a duel is not enough. A Hate. The holy and sacred declaration of Revenge.

— The Duel

There are circumstances when a duel will not satisfy honor. When an injury is so egregious, simple combat will not heal the wound. An elaborate plan to discredit and dishonor. A beloved friend proves to be a treacherous enemy.

Hate. The Old Tongue. The heart is possessed by a black spirit. Hungry. It can only dine on retribution. To satisfy the Hate, one must undertake Revenge.

This is not analogy or allegory. The ven believe the magic of their blood creates a spirit that swims through their blood, poisoning all it touches. They grow ill. They cannot eat. They cannot sleep. Consumed by Hate, action must be taken. The only action that can cure the sickness.

Revenge. The only cure is the cause.

I have to emphasize again that revenge is something too powerful for trivial use. In his entire life, a ven may declare revenge once. Perhaps twice. But, as the boy who cried wolf has taught us, one who abuses privilege too often finds himself stripped of that privilege. In the five volumes of Shara’s adventures, I found two instances of her declaring Revenge. Granted, we no longer have Volume 4, but Volume 5 makes no reference to revenge in its summation of the tale so far.

A noble who declares Revenge at every slight will find himself cut off from others. Bad form.

To undertake Revenge, a noble must go through the following steps.

THE LETTER

First, he must write a letter describing both “the cause and the cure.” This is ven poetry for

- what caused the revenge, and

- what will bring the revenge to an end.

This is a sorcerous ritual, written in the offended party’s blood. You can find the details of the ritual in the Sorcery chapter.

PERMISSION

Second, he must seek permission from his liege. Written permission. If a noble has no liege, he must find a higher ranked noble from his own House to sign the document. In his own blood. This seals the document.

If a liege refuses to sign the document, Revenge cannot proceed.

ANNOUNCEMENT

To properly declare Revenge, a ven must go to the Senate and do so. As is tradition, a ven must wear something red. A rose, a scarf, a handkerchief. The declaration is read before the members of the Senate (the Law states at least half the members must be present) and the Senate chooses five members to judge the validity of the Revenge. At least three of the five members must vote in the positive to legitimize the Revenge.

If the matter is declared “untrue Revenge,” the issue is over. There is no appeal.

If the matter is declared “true Revenge,” the ritual begins.

- First, the council of five declare how long the Revenge will last. One week, two months, a lifetime. The offended party can ask for a period of time, but it is up to the council of five to decide.

- Second, both parties must spill blood on the document. Yes, this is a public use of sorcery. One of the few instances when sorcery is legal. You’ll find out why in a moment.

- Third, both parties are given one week to prepare. Just seven days.

- Fourth, the Senate announces the Revenge to the general public.

THE PATH OF BLOOD

Now, the Revenge has begun. And what’s so special about that?

Well, to begin with, during the time of Revenge, both parties must identify themselves by wearing red. A red rose, red handkerchief, etc. Just like above.

While the Revenge is active, no laws apply to the two under its shadow. No laws. Robbery, thievery. None.

Nothing must stand in the path of the Hate. Nothing must stand in the way of rightful Revenge.

Anyone who interferes in a Revenge—protecting one of the parties, giving shelter, aid, comfort, whatever—becomes part of the Revenge. They do not gain any of the benefits, but lose any legal recourse from injury that may befall them because of their interference.

In other words, if you meddle in someone else’s business, you lose all legal rights and they gain the right to kill you on sight.

Another detail. While under the shadow of Revenge, neither ven can wear a sword. Daggers. That’s it.

The Revenge continues until the time runs out or one of the two is dead. That brings up a questions I’m sure some will ask. “Can more than two people be involved in a Revenge?”

The answer is no. Two ven. One declaration. That’s it.

If time expires and the Revenge has not been fulfilled, the affair is over. It may never be mentioned again. Done. Finished. Over.

Hold a grudge? Bad form.

Try to use it as leverage? Bad form.

Use it to gain advantage? Bad form.

Once Revenge is over, it is over. Done. Finished. Over.

THE PATRON SAINT OF REVENGE

One more point about Revenge before we move on.

The suaven Ikhalu. The patron saint of Revenge. His temple stands in the capital, just under the shadow of the Senate. His priests wear his robes. Silver masks. Daggers.

A ven who comes to his temple seeks only one thing. Ikhalu’s Blessing for Revenge.

Prostrate before the suaven, begging for his Blessing. Waiting for the call.

Some spend months. Years. Waiting. Just waiting for a whisper.

Only a few hear him. Only the righteous. The desperate are cast away. The desperate become the hopeless.

If granted Ikhalu’s Blessing, no ven can deny the right of Revenge. No ven. No baron, no duke, no count, no senator. No father, no son, no daughter, no husband, no wife.

Wearing Ikhalu’s mark—the black eyes reflecting the Hate that swims in their blood—shows the truth.

“I belong to he who whispered Revenge into me.”

No one dare deny Ikhalu.

Rage Against the Al

Two great tastes that taste great together.

Super Heroes!

This American Life has an episode with a super hero theme. Once again, this amazing radio show kicks my ass.

You can listen to it here.

(Thanks to Daniel Friggin’ Solis.)