No bullshit. No exaggeration. No kidding.

EDIT: It has since been pointed out to me that this link has been taken entirely out of context. I was suckered.

Go intarweb.

The Tao of Zen Nihilism

No bullshit. No exaggeration. No kidding.

EDIT: It has since been pointed out to me that this link has been taken entirely out of context. I was suckered.

Go intarweb.

(in the key of Randy Newman minor)

If I had cancer, I’d be losing weight and my hair

If I lost an arm, it’d be easy to see

If I had jitters like Marty McFly

I wouldn’t need to explain why

But I can’t

I can’t

God knows I’ve tried

But you know what they say about trying

There’s a thing in my head

(You’ll have to trust me on this)

But it’s in there and it isn’t going away

Not now and not tomorrow and not the next day

It has a mouth and it has teeth

And its eating all my words

Sad thing for a writer to lose all his words

But that’s what’s happening to me

You can’t see it but it’s there

(You’ll have to trust me on this)

It’s something you just can’t see

It ate my marriage

Its eaten my friends

Ate a book I was supposed to write

And you’d think it would be happy with that

But it isn’t

It just keeps on going

And it won’t stop

No, it won’t stop

It won’t stop

Even if I beg

It gets into my arms and legs

Gets into my mouth

And I watch it

Just like it watches me

Pretty soon there won’t be anything left

Just me and it

No words

No memories

Ntoinhg

It ate my marriage

Its eaten my friends

Ate a book I was supposed to write

And you’d think it would be happy with that

But it isn’t

It just keeps on going

And it won’t stop

No, it won’t stop

It won’t stop

Even if I beg

If I had cancer, I’d be losing weight

If I lost an arm, it’d be easy to see

But it haven’t

Maybe if I did it would make it easier to believe

It has a mouth and it has teeth

And its eating all my words

Sad thing for a writer to lose all his words

But that’s what’s happening to me

______

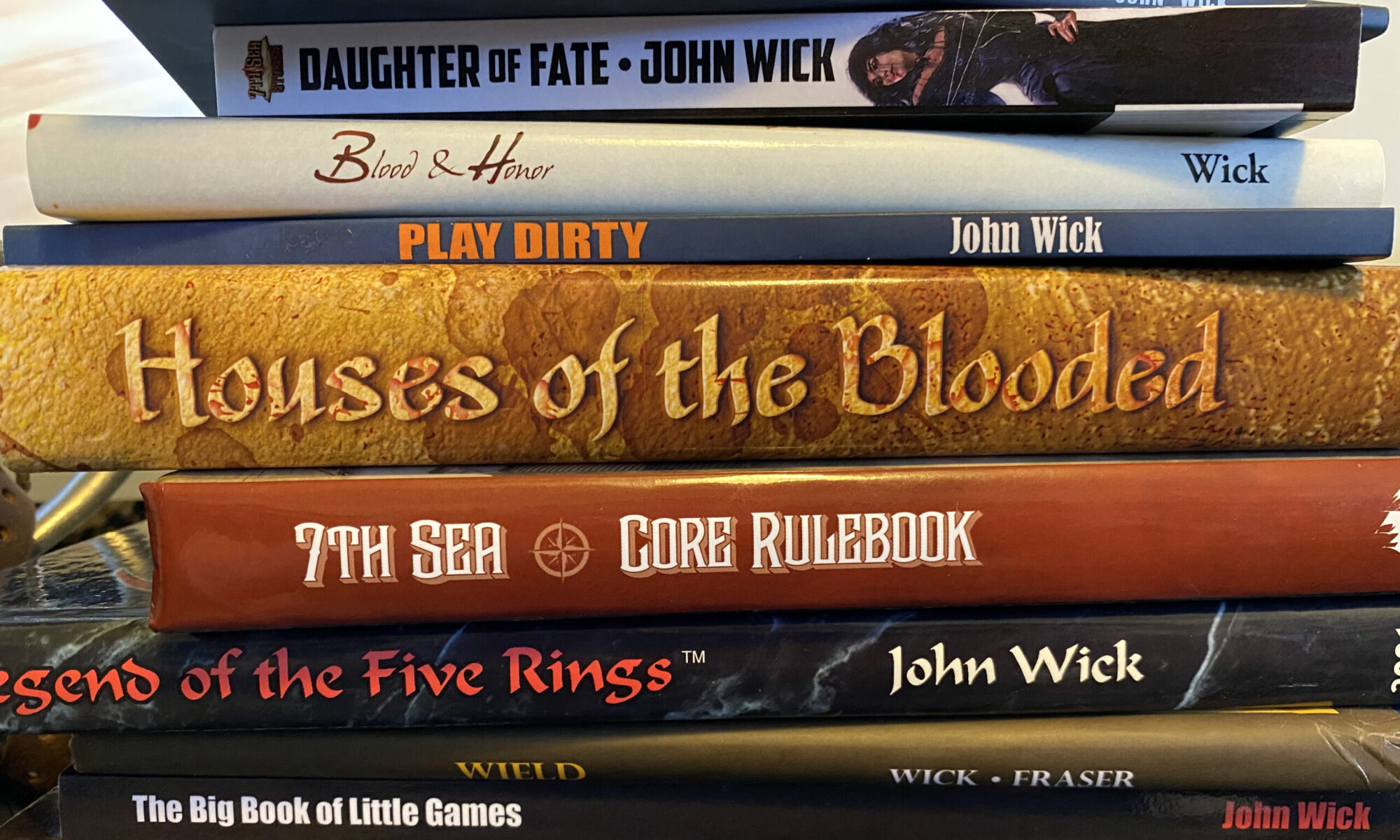

More Houses of the Blooded tonight.

When I was in high school, the biggest open secret was the sociology teacher’s quizzes. His quizzes were always multiple choice and everybody knew that if you answered “D” on his quizzes, you’d get a C. He designed them that way. All you had to do was answer “D” on each and every question and you’d pass his class. And so, in honor of that great tradition, I give you this pop quiz.

1) In the world’s most famous RPG, which mechanic represents insignificant injuries, dodging, glancing blows deflected off armor, and lucky misses?

a) hit points

b) armor class

c) difficulty class

d) both a) and b)

2) In the world’s most famous RPG, which mechanic represents taking a serious blow?

a) going to zero hit points

b) an opponent defeating your armor class

c) alignment

d) both a) and b)

3) In the world’s most famous RPG, what two mechanics are redundant systems?

a) hit points

b) armor class

c) speed factor

d) both a) and b)

When Dave Arneson designed the combat system for D&D, he modeled it after a naval combat game. (You can read the Mighty Mighty Arneson talking about it here.) From that perspective, it makes sense. You have to get through the armor of a ship to hurt it. But for one-on-one combat, it makes less sense. The systems become redundant.

Now, to be fair, we are talking about the very beginning of RPG design here. Dave, Gary, Dave Hargrave, Steve Perrin, the Troll Lord and the Great and Mighty Stafford were really just making all this up as they went. Shooting in the dark. We’re talking primitive technology here, but it was as innovative as the wheel. Others built on the foundation they laid, and technology has progressed. So, let’s do just that. Let’s build on what’s come before.

Injury

My buddy Matt Colville and I were arguing about hit points. Matt told me that he liked the fact that characters take no penalties for actions until they fall because, “When I need to be heroic, I can be.”

In other words, using a death spiral discourages heroic action. When things are at their worst, heroes are at their best. This is a literary conceit both Matt and I like very much. Death spiral systems discourage this kind of action in a roleplaying game. That’s why, in 7th Sea, there is no death spiral.

But death spirals do add a sense of dramatic tension to the game… and, dare I say it, “realism.” When you get hurt, it’s harder to act. It’s harder to keep going, to push through the pain. That’s a different kind of heroism. And that’s why, in L5R, there is a death spiral.

So, how do you do both? How to give a player the sense of “my character is really hurt” while allowing a character to be heroic when he needs to be? Well, first, you provide a mechanic (aspects) that allow him to call on bonus dice when he needs them. Okay, we’ve got that. But we also need a mechanic that warns the player, “Your character is really hurt. You need to protect yourself or something very bad is going to happen.”

Aspects.

When your character gets hurt, you gain an injury aspect. Or, just injury, if you like. The injury has a rank equal to the effect of the attacker’s roll. In other words, if someone attacks your character and his hit is worth 3 effect, that injury is rank 3.

For example, your character is in a duel and he gets hit with the business end of a sword. When the rolling is done, the total effect is 3, you write down the injury on your character sheet. (There’s a spot for injuries. Go look.) The attacker gets to define the injury. A cut across the face, a slice across the wrist, a jab to the belly, whatever.

Now, that injury can be invoked once per round by one opponent. Invoking that injury either gives him a number of bonus dice equal to the rank of the injury or subtracts a number of dice from your next risk. His choice. Remember: if you cannot roll dice for a risk, you automatically fail that risk.

Getting Dead

This leads us to how a character actually dies… which you don’t get today. It’s a different mechanic I’ll be dealing with tomorrow.

Hey, you rolled a 20! You get a crit!

Well, not really. It isn’t rare enough that a crit only happens 5% of the time. We’re going to make you roll again to make sure you got a crit. And while you’re at it, get a copy of the dictionary, open it up to “anti-climax,” then smack it upside your own head.

And even if you do get a crit, you can still roll shit for damage. Roll a 1 and you get–Gods Alive!–a grand total of 2 hit points! Yeah, that makes me feel like a hero!

With that in mind, let’s come up with a system that lets players call their own critical hits and let’s make critical hits actually mean critical. How do we do that? Let’s take a look.

First, when you attack an opponent, you roll a number of dice equal to your character’s Prowess+The Sword+any other bonus dice against your opponent’s dice pool. That’s usually Prowess x 3 unless he makes an active defense. In that case, he rolls a die pool and the highest roll wins.

If the attacker succeeds, damage equals his Strength+Weapon. But, the attacker can wager dice (remember wagers?) to increase the effect of his attack. Every die you wager before the roll adds one to the damage. That’s base damage that you always get when you succeed boosted by your wagers. You take the risk, you reap the reward… or the consequences.

Player choice. Choosing how many dice you set aside to decide when you act, setting dice aside to boost your effect. Getting a better look at that big picture?

I’ve got another idea that I’m toying with, but it isn’t ready yet. Maybe more tonight.

Game design is about choice. Giving the players multiple choices, each of which seems the Best Choice.

Take Feats for example. There are some Feats that you’ll never take. Just never. You look at them in comparison with other Feats and the choice is obvious. Alternately, in the Bungie game HALO, the Master Chief (that’s you) can only carry 2 weapons at a time. And at every point during that game, you wish you could carry three. All the enemies respond differently to different weapons. Human weapons work best on The Flood, Covenant weapons work best on the Covenant, and you never EVER want to ditch the pistol… unless there’s a rocket launcher. Or the shotgun. And DAMMIT! I need three hands!!!

Game design is about choice. But you can put too many choices in front of the player, resulting in frustration. Frustration is not fun.

Choice/Frustration. Difficult balance. But when you find it, you’ve got it. Great game design.

“Going first” has long been a source of frustration for me. The Dice Gods hate me. No shit, I mean they hate me. Must be a family curse or something because when I go to visit my folks in Vegas, my dad don’t play craps, he plays blackjack. He loses at craps. He wins at blackjack.

And so, whenever it is time to “roll initiative,” I always come in last. I roll the lowest possible result. It doesn’t matter how many choices I made in designing my character, the dice betray me. Every time.

And so, how do we make going first less about arbitrary randomness and more about choice? How’s this.

When a fight scene begins, everyone decides how many dice they’re going to give up to go first. The number of dice you pick is the number of dice you lose from your next action. The person who gives up the most dice goes first, followed by the person who gives up the next highest number of dice, and so on down the line. Ties go simultaneously.

For example: Albert, Bob, Cindy and Dave enter a fight scene. Albert gives up 3 dice, Bob gives up 2, Cindy gives up 3, and Dave gives up no dice. Because Albert and Cindy both gave up the most amount of dice, they get to go first, losing 3 dice from their next action. Because Bob gave up 2 dice, he goes second. Then, Dave goes last because he gave up no dice at all.

You want to go first? It’s going to cost you accuracy. Speed costs accuracy. (I got this idea a long time ago when someone asked me how I’d do a wild west rpg and Unforgiven was on my mind.)

A few kickers.

First, the bidding of dice is secret. Nobody knows how many dice folks are giving up to go first. (If players want to metagame and decide among themselves who should give up how many dice, I approve. It’s called “having a plan.”) Dice are revealed at once.

Second kicker. Giving up dice at the beginning of a fight scene means you have to think about what you’re going to do. You have to think, “Ok. I want to attack that guy over there with my sword. I’ll roll nine dice. I can give up three of them for a speed.” Of course, no plan ever survives direct contact with the enemy, so what you end up doing will, more than likely, not be what you intended to do. Giving up dice blind at the beginning of a fight means you’re betting on getting to do what you wanted. You counted on attacking, but end up doing something else… but you’ve still got to lose the same number of dice.

Choices. That’s what game design is about. Making players measure choices. And forcing them to improvise when plans go wrong.

Why do fight scenes take four hours of real time with hundreds of rolls, endless accounting, and an overly anal obsession with detail… while seducing the barmaid is just one single roll?

Obviously, such rules were written by virgins.

But seriously…

I said at the beginning of this whole thing that HotB was designed to address what I felt was missing from the world’s most famous RPG. In most RPGs, fighting is obviously very important. After all, what takes up the bulk of nearly every rule book? Fight scenes. What takes the most amount of time? Fight scenes. What do adventures focus on? Fight scenes.

Nothing is more dangerous than putting life and limb on the line, and like that old Cerebus joke, there’s nothing that builds character more than CONFLICT!!!

But does a fuukin heeeuuuge combat system make fight scenes more important… or less important? Think about it.

In a way, presenting a fight scene as a rigorous, highly regimented, highly organized point-by-point, second-by-second exercise of tactics and strategy really doesn’t do fighting any kind of justice. The fact is that fights are messy, uncertain, brutal events. Not only that, but a fight is over before anyone anticipates. They don’t go on for hours and hours. Fights are decided in seconds, and usually, nobody involved “wins.”

Sun Tzu based his treatise on a single principle: defeat your enemy before it comes to blows. Walk into a fight with the absolute certainty that your enemy cannot win. He was successful because he knew that once the fight starts, all bets are off. If you get in a fight without a plan (and seven different contingencies for when, not if but when, your plan goes wrong), the cost of fighting will overwhelm the reward of victory.

Turning fight scenes into tick-tock excercises of hum drum mathematical equations doesn’t even approach the reality of a fight. Just like the barmaid, such systems look like they were written by people who have no clue what a real fight looks like. More importantly, what a real fight feels like.

I direct the reader to two movies. The first is David Fincher’s Se7en. Watch the chase scene in the second act when the two detectives race after a potential suspect in the movie’s brutal murders. The scene is dizzying, difficult to follow, and feels dangerous. This is deliberate. Fincher hated chase scenes where you always knew where everybody was, always had a clear field of vision and saw all the scenes from every point-of-view. And thus, the beautiful, lyrical mess of a chase scene.

The second film is Oldboy. There is a fight scene in that film that perfectly captures what I’m talking about. It feels like a fight should feel. Not a choreographed rhapsody of movement that feels like an opera, but a bloody and brutal battle. (Sorry for the illiteration.) And the protagonist’s weapon is a hammer. Just a hammer. I will say no more.

Clint Eastwood was asked about the realism of his films. He said he wasn’t interested in being realistic, but authentic. To make the viewer feel the truth of the piece. My goal with the fight scenes system in HotB isn’t to present a “realistic” combat system, but an authentic one. To make the players feel like they’re in a real fight. A dangerous situation that could take an unexpected turn any second.

This is the system I want. I’ll be working slowly toward it. Later on tonight, we’ll take the first step.

I do not have the time to post the entire entry–it is over 8,000 words and won’t fit here–but I will let you know that “Saints and Secrets” will be replacing the entire Advantages section of the book.

Essentially, it breaks down like this.

Advantages like “Large” and “Left-Handed” and other such mundane things are now Aspects. (As they should be.) Advantages like “Spy Network” and “Seneschal” are going to be a different kind of trait that I’ll cover later.

On the other hand, players get 5 points to spend on saints: the shuaven. Each shuaven has a number of “secrets” they can teach your character. The secrets are based on theme. Fighty saints have fighty secrets. Sneaky saints have sneaky secrets. Beautiful saints have sexy secrets.

Faithful readers (those who own at least a .pdf of Enemy Gods) will recognize some of the saints–although in slightly different iterations. Falvren Dyr and Talia are definately there, as well as the “blessings” they gave to faithful followers.

Ven gain the secrets through Devotion: proving their dedication to the saint’s mystery cult. As your Devotion to a saint increases, so do the secrets he will teach you. If your Devotion decreases, access to those secrets will be cut off.

I’ll be posting the saints and their secrets later in the week. I need a break from completely revising a vital part of my game. I’m moving on to systems this week, starting with Fight Scenes which should be up later today.

I’ll be doing something entirely different with Advantages. I’m not exactly sure what it is just yet, but I’ll let you know next week.

Saints and Secrets later today.

(Mechanics tonight. For now, you get the idea.)

The ven do not die of old age. Instead, their bodies slow, their blood cools, and their skin begins emitting a strange substance called altrua. Altrua is not unlike spider’s webs. Over the years, they fall into a state they call “solace.” Eventually, the entire body goes into hibernation, wrapped up in altrua, asleep. And dreaming.

The ven believe the mind of a ven in solace is still aware. In fact, while in solace, the ven mind becomes incredibly powerful, capable of transmitting thoughts and visions to those of kindred blood and spirit. The ven receive these visions while dreaming themselves, but they can also learn how to place their minds into an altered state that is able to receive these messages of dreaming ven.

Those who slumber in solace are called shuaven: the dreaming ven. Revered by their Houses, they become the equivalent of our own patron saints. The ven pray to them at shrines, collect artifacts from their lives, and maintain the sleeping body. While the shuaven is protected within his altrua shroud, his is not invulnerable. Altrua is particularly vulnerable to fire and many shuaven has been lost in such a way.

The shuaven are far from equal and not all are universally revered. The worship of some shuaven is small: they are only revered by their families. Other shuaven, however, have temples in every city on Shanri. Their names are whispered only in reverence, sung with open throats, and feared by every sensible ven.

Most ven often find a kind of communion with a particular shuaven—sometimes a saint not even of his own House. In order to gain a deeper understanding and to make the bond between them stronger, many ven join mystery cults devoted to the shuaven.

All the shuaven are different. What is true of one is most likely not true of another. Some are revered while others are worshipped. Some have temples and others have perhaps one or two shrines. A few shuaven have even been forgotten, lost in the catacombs under the thriving metropolis, they wait, sending visions to those who might hear, hoping one day hey will be rediscovered.

And then there are the fashuva: the fell ones. Even whispering their names is dangerous. We shall not speak of them here, lest they hear us. Even mentioning them could call their attention. We shall say no more.

My temp agency sent me to the Santa Monica MTV offices today for a job I am completely unqualified to do. That’s okay; they were too busy to train me today, so I sat in front of a computer screen and read the Amazing and Brilliant Dictionary of Mu.

(Trust me when I say this. Your game shelf is barren without this game. Lacking. Empty. But take care: this book will beat the holy hell out of your other books if you leave it alone too long.)

When my shift was done, I went down to the lobby to get my parking validated. A long day. Boring, yet exciting. Energizing, yet draining. Inspired and restless. The security guard was on the phone, so I had to wait. The very cute girl behind the counter…

… wait a second. Let me say this about working at MTV. Every single person in that office is hot. I mean it. I felt like a raisin in a county fair grape contest. Damn, damn, damn. Anyway…

… chatting with the girl behind the counter. She apologizes and blushes because the security guard is on the phone with his girlfriend or something and “too busy” to validate my parking. The elevator doors behind me open and She steps out.

Her hair and eyes. Her lips. Her smile. I’ve heard say that Hollywood thinks she’s not skinny enough. Hollywood can go fuck a mop. Better yet, a vacuum cleaner. She steps out of the elevator, and I’m stunned. Floored. I don’t know what to say. Her eyes look up at me…

… and she recognizes me. Wait a second. What the…

“Hi!” she says with that excited voice of hers. And she walks quickly across the lobby, straight toward me. “How have you been?”

And now, right now, Discordia is in my head. And she’s laughing. Laughing so hard, I can’t hear the security guard talking on the phone or the gasp of the cute girl behind the desk, or even the sound of my own heart. Discordia is laughing. And She’s telling me exactly what I need to do. Right now. Do it, John. Do it. Right now. Right now. Right. The. Fuck. NOW.

But Discretion wins out. And just before she reaches me, I give a friendly, apologetic smile and as charming as I can, I say, “I’m sorry, but, you don’t know me.”

She stops, just a few steps away from the hug I was about to get. And she looks at me again. Closer. Hearing my voice. Then, her eyes go wide and her face goes red. Pure red.

“Oh!” she says. “I’m so sorry.”

I laugh. “It’s okay,” I tell her. “I get it all the time.”

Then, she finds a nervous laugh in her belly as her people usher her away as fast as they bloody well can.

And all I can hear is Discordia saying, “You should have listened…”